Viv, Larry, and the Great Anglo-American Film War

Or How Laurence Lorded It Over Leigh in a “Truly TARIFF-ic Absolutely True Story”

“...Treasure of Sierra Madre, Warner Brothers. And the winner?”

An attendant pressed 1948’s Best Picture envelope into Ethel Barrymore’s hands. Barrymore, the formidable matriarch of a theatrical dynasty, received a warm ovation. A beloved old lady of stage and screen – think Nathan Lane today – she was every inch the profession’s elder stateswoman. On this night of nights, when Oscar reached the majority age of twenty-one, who better to present the final award?

Her disappointment was barely masked. The grande dame blanched, and, under bated breath, hissed:

“Hamlet. J. Arthur Rank, Two-Cities Films.”

Conventional wisdom claims she found Sir Laurence Olivier’s interpretation of the hesitant prince inferior to her brother’s. At seventeen, Larry saw John Barrymore’s London production. The actor who, in his view, single-handedly “brought the balls” back to the Dane. He appropriated the American’s “burningly real” characterisation. A raw, modern take, Olivier soon eclipsed his predecessor’s in renown.

His journey began twelve years earlier. First in the West End in January 1937, and, later, at Kronborg Castle, Helsingør. Sadly, torrential rain banished Larry’s troupe from the ramparts of Elsinore to the nearest hotel’s ballroom. Ophelia, initially portrayed by Cherry Cottrell, was recast. Some claim Cottrell was unavailable; others allege she was deliberately passed over. “Did Hamlet sleep with Ophelia?” It’s a question that’s hounded Shakespeare scholars for centuries. “In this company,” Olivier deadpanned, “always.” For the Danish run, he selected a young starlet who’d watched his performance at the Old Vic fourteen times. A London lawyer’s wife, Trilby to his Svengali. Mrs. Leigh Holman. Better known to us, of course, as Vivien Leigh.

The greatest Best Actress champion is unquestionably Vivien Leigh. The second greatest? Her again.

Laurence Olivier won an acting Oscar and two honorary ones. The American Film Institute ranked him the 14th top male screen legend, two places ahead of Vivien among actresses. And, for all that, I’ve always considered the knight-errant, well, hammy. At least in the early years: where a putty nose or eyepatch does the heavy lifting. He tackles Heathcliff like the principal boy in a pantomime! “Olivier” is synonymous with theatre, down to his namesake awards, but the camera adored Vivien Leigh.

After Scarlett, she could’ve triumphed in every significant female role on screen. Sequestered in wartime England, that became impossible. Katharine Hepburn, maid of honour at their 1940 marriage, offered shrewd observations on the couple. “Larry always wanted to be a movie star. And while he was considered the greatest actor on the stage, he was never in the first rank in the movies. Then Vivien comes along and gets Scarlett O’Hara. Wins the Academy Award. Biggest picture ever made. Suddenly, Larry says, “Oh darling. We really must get you out of Hollywood now. Let’s go off and do Shakespeare together”.”

This dynamic explained their absence on Oscar Night ‘49. They were performing a farewell season of rep in St. Martin’s Lane. Olivier, no doubt, welcomed the opportunity to dodge it – sparing his ego from bruising. Leigh was revered as royalty in America. Nine years prior, Vivien won Best Actress for Gone With the Wind, but the knight, up for Wuthering Heights, lost Best Actor to Robert Donat, not Clark Gable. In a fit of envy, he seized his lady’s gold man. “It was all I could do to restrain myself from hitting her with it,” he confessed to his son Tarquin in My Father, Laurence Olivier, “I was insane with jealousy.” At a subsequent gathering, he hurled it into the yard.

Some men can’t handle their spouses outshining them. This enmity was nothing new. It simmered long before Vivien’s star rose, and would surface again with his future wife, Joan Plowright. Indeed, in 1932, Katharine Hepburn saw the conjugal envy up close. Larry, a clergyman’s son, took for his first bride Jill Esmond, a closeted lesbian from an acting family. The newlyweds tried their luck in California, but while the former Mrs. O easily found her footing, Larry was a non-starter. Sacked from Garbo’s Queen Christina, he whisked Jill back to London. He snuffed out Esmond’s burgeoning career and blocked her opportunity to lead A Bill of Divorcement – Hepburn’s big break.

The second Mrs. Olivier maintained that her celebrity never soured their relationship. For he was the superior talent. Vivien made no pretensions to actorly brilliance. She was an English beauty who’d won an Oscar.

When the Academy tossed her husband a special award for the morale-boosting Henry V, unseen in America until 1946, Viv threw a party. The freshly ennobled Sir Laurence was furious. He regarded it as an “absolute fob-off”. “Best Actor was still going, Best Director was still going, Best Producer was still going.” (He conveniently omitted that his nominations were only for Best Actor and Best Picture, with no directorial nod.) To him, this was a bald manoeuvre to clear key categories for a different film’s victory. Regardless, he ensured the moment was captured for posterity; posing in full Hamlet regalia with the consolation prize. What’s more, he allowed his wife to make a fuss, knowing that such celebrations eluded hers.

Olivier bided his time, and within two years, he was rewarded with the genuine article.

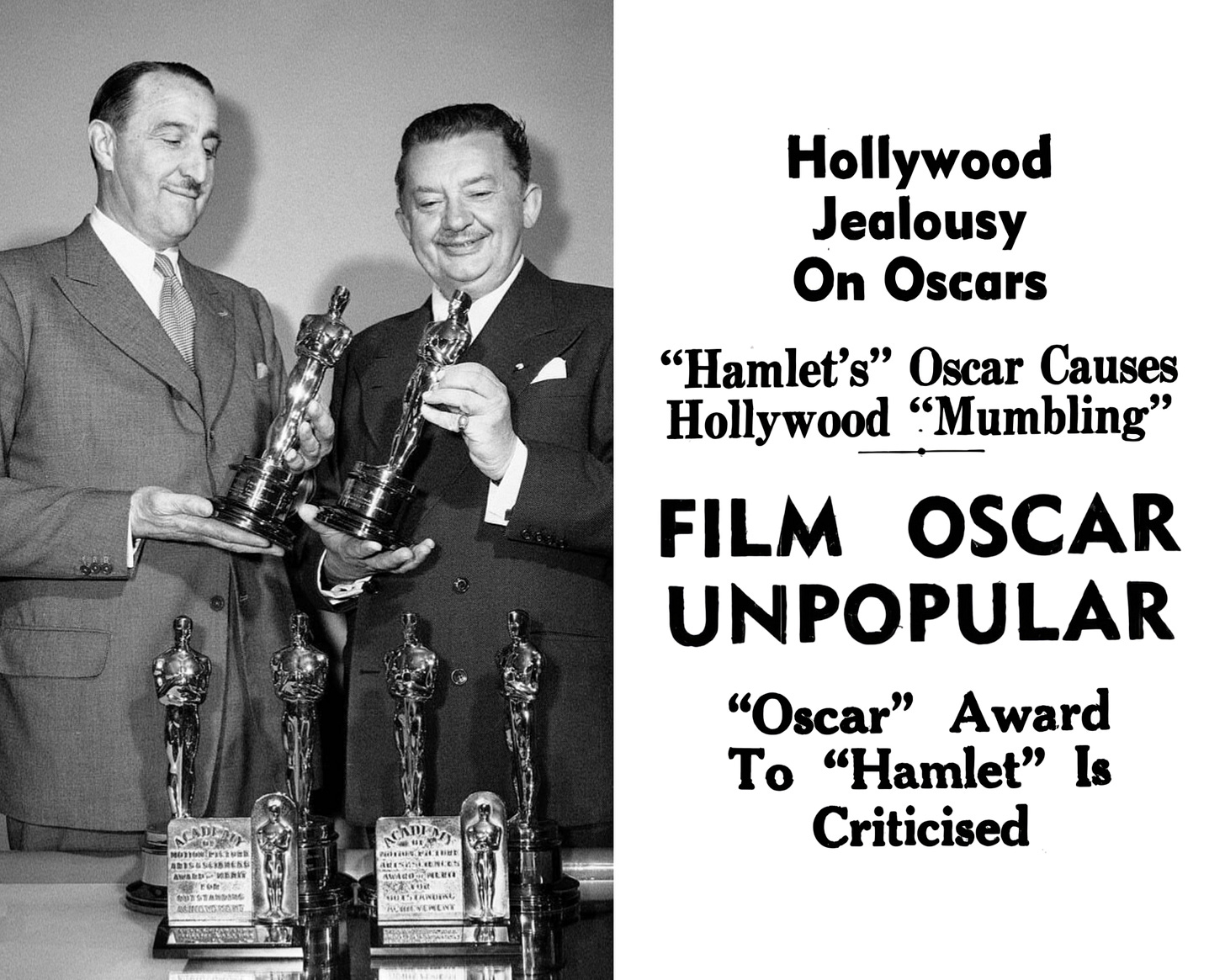

The debonair Douglas Fairbanks Jr., an Anglophile and the first Mr. Joan Crawford, shuffled onstage to accept Hamlet’s Best Picture statuette. Having silently collected his friend’s Best Actor, it was his second appearance in five minutes. This time, he was goaded to say a few words. Alas, inspired by Ethel Barrymore’s unimpressed hauteur, the crowd was thinning faster than my hairline.

For the first time, a film financed entirely outside the United States prevailed. An achievement that rippled through an industry rife with Anglo-American tension. With J. Arthur Rank’s The Red Shoes also cited, two nominees were British – a history-making precedent. Combined, Rank’s efforts won the most gongs of the night: leaving the homegrown Johnny Belinda, The Snake Pit and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre in the dust. And for an Academy in one of its perpetual identity crises, this was hardly the desired outcome.

Weary of the parochial response, Olivier’s proxy reminded the dwindling audience that the actor-director “had lived and worked among us for so many years”. Fairbanks tapped into a timeless sentiment. The common desire for peer recognition. Among Sir Laurence’s honours, “none can be more touching or more gratifying than from his own profession”. He closed by saluting the Academy for choosing him twice, as newspapermen bolted to chase front pages.

Not that many were present. Indeed, due to limited seating, even Hollywood’s Old Guard listened in on the wireless. Quashing rumours that they’d been rigging the awards, the major studios – MGM, 20th Century Fox, Warner Brothers, Paramount, and RKO, who’d hitherto underwritten the gala – pulled support at the last minute. Without time or money to rent a large venue, the Academy staged the event at their Marquis Theatre on Melrose, renamed the “Academy Awards Theatre” for the night. Moguls like Louis B. Mayer and Darryl F. Zanuck justified ending their sponsorship as a noble act against gamifying and commercialising art. In reality, it was a cost-cutting measure. Then a closed shop, the Academy could shield their backstage brouhaha from the press.

Paper never refused ink. “Prides had been wounded by the bombshell bestowal of the Academy Award upon Hamlet,” wrote Bosley Crowther in the New York Times. The post-ceremony secession of three minors (Columbia, Universal-International, and Republic) from Oscar’s investors ensured this dirty laundry was aired. Britain’s breakthrough proving the knockout blow to local patience. It was easier to find the unaltered cut of Judy’s A Star is Born than a Hamlet voter! Journos did manage to dig up a Columbia executive, who sighed: “It looks as if the Academy Awards is going to fold”. “The timing,” Crowther continued “of the studios’ exposé sounds like very sour grapes.”

Eager to cement his legacy as the departing executive, Academy president Jean Hersholt used the silly season as a way of shaming the Big Five (and Little Three) back into the fold. The Academy fed the press a series of counter-missives. First, Oscar host Robert Montgomery denounced the “bad sportsmanship” that erupted following Hamlet’s selection. Editorials highlighted studio hypocrisy. Exploiting the laurels for publicity, while refusing to fund them. The sucker punch worked. The Mayers and Zanucks opened their coffers once more. On a year-by-year basis, mind you, fuelled by capitalist greed. A fortuitous Dow Jones study alerted them to Oscar’s economic potential. Box office for The Best Years of Our Lives and Gentlemen’s Agreement, the Best Pictures of 1946 and 1947, soared after their wins. Isolationist protectionism held firm. With no interest in sending that money overseas (even David Lean’s winning epics would rely on Sam Spiegel’s Hollywood financing), all-American fare dominated for a generation.

On the eve of his retirement, Hersholt personally presented the six British Oscars to J. Arthur Rank, grandee of Pinewood, mending strained transatlantic ties.

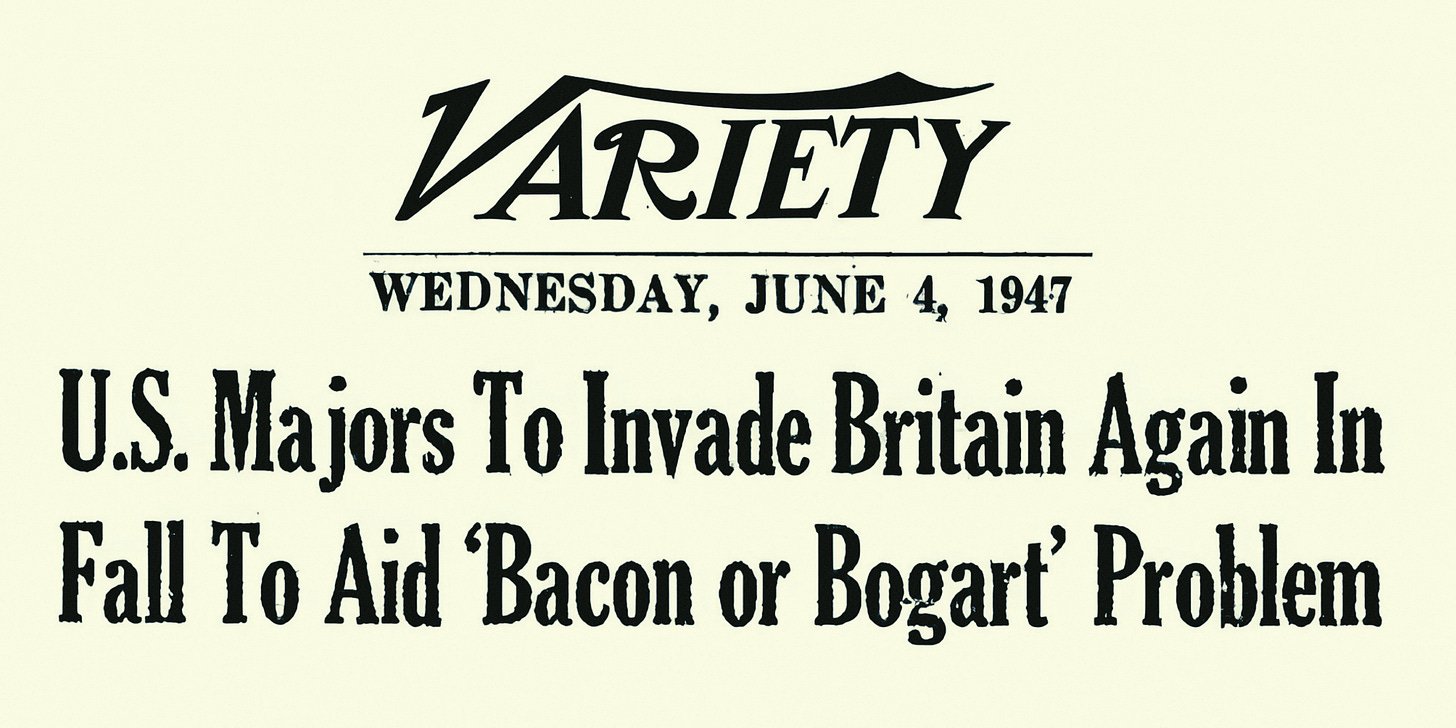

“Bogart vs. Bacon”, wags called it. Or the “Great Anglo-American Film War”. More of a fleeting skirmish. In 1947, the British Board of Trade imposed a swingeing import tax on American movies. The “Dalton Duty”. After Hugh Dalton, Chancellor of the Exchequer. Amid postwar austerity, Dalton sought to strengthen the domestic film business and oppose Hollywood control. As viewers of the Talking Pictures TV Channel will recognise, prestige flicks from this era – Hamlet, Black Narcissus, Great Expectations – were outliers. London’s speciality was unwatchable “quota quickies”.

A displeased Truman administration retaliated by halting film exports to the United Kingdom until the duty’s repeal in spring 1948. Naturally, the boycott’s impact was minimal. There was plenty of surplus American hokum to fill British fleapits in the intervening eight months. Scarcely enough time, either, for the limeys to establish a robust, self-sustaining production model of their own. In any case, J. Arthur Rank, guided by Methodist scruples and intent on producing family-oriented films, held a virtual monopoly. Nonetheless, it was a “war” and in a war, there are always casualties.

As much as Olivier’s Hamlet was a triumph, Vivien Leigh’s offering for 1948, Anna Karenina, was an unqualified disaster. It simply wasn’t good. Cecil Beaton’s costumes cannot compensate for a film where nearly everyone is miscast. This depressing episode weighed heavily on Vivien, as did her recent recovery from tuberculosis: the affliction that would torment her until her death at fifty-three.

Hindered by tariffs and barred from the American market, Anna Karenina recouped a minuscule fraction of its budget. (One hundred percent of foreign profit was lost.) Having returned to England at her husband’s urging in 1941, twenty-seven-year-old Vivien unwittingly squandered Scarlett O’Hara’s clout. Still strikingly beautiful at thirty-five, she was conspicuous among the plainer women of Britain’s kitchen-sinks: Celia Johnson or Googie Withers. After Gone With the Wind, she made only eight films. With two exceptions, they’re all noble failures.

“A few years pass and Vivien returns to make A Streetcar Named Desire,” Katharine Hepburn recalled, “and she’s brilliant. Wins the Academy Award. Most talked about movie of the year. And suddenly Larry says, “Oh darling. We really must get you out of Hollywood now. Let’s go off and do Shakespeare together”.”

It’s all cyclical.

Was Larry happy that his wife was relegated to consort? Hepburn certainly thought so. “Vivien could do anything,” Kate recalled, “but he was clearly trying to keep her in her place, which was billed beneath him. Small man.”

Hamlet’s Oscar, shaped by Sir Laurence Olivier’s ambition and Vivien Leigh’s sacrifice, brimmed with more intrigue than Shakespeare’s tragedy. A defining moment in a turbulent marriage at its halfway mark. (They’d divorce in 1960.) Oscillating between fierce love and bitter rivalry, their struggle mirrored broader UK-US discord for the silver screen’s crown. Larry’s Dane may have temporarily silenced his insecurity, but Viv’s Scarlett (and Blanche) outshone it in enduring fame. His theatrical brilliance fades against her cinematic legacy. A contrast Katharine Hepburn framed sharply.

“Giant actor. Very small man.”

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew!

Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d

His canon ‘gainst self-slaughter!

— William Shakespeare, “Hamlet”

Read Next:

Richard Chamberlain and the Politics of Outing

I Know Why the Songbird’s Caged

Cottagecore: Or How Sir John Gielgud Went to the Gents’ and Almost Lost It All

Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the (Revolution in France) Oscar Nominations, 1955

My Supporting Actress Series:

Vanessa’s Varicose Veins (1977)

Hattie McDaniel’s Legacy (1939)

Olivier's life seemed to be an example of "be careful what you wish for," and once he got it he never seemed to enjoy it. I thought he was perfect in Rebecca but am not really a fan of most of his other films, mostly because you can always catch him acting. Vivien Leigh, IMHO, is a far superior screen star and actor, and I can never take my eyes off her even in the miscast Anna Karenina, where she looked and and acted beautifully. She had "it" on the silver screen, which makes a great star, and it is a pity she made so few films. I enjoy your writing and look forward to reading more of them. Cheers~

Seems like he was nostalgic for the original Shakespeare…before women were allowed on stage. Too fragile for women.