The picture you’re ga(y)zing at depicts Judy Garland, Jane Wyman and June Allyson at NBC’s broadcast of the 27th Oscar Nominations in February 1955.

Yes, you read that correctly.

In the mid-fifties, the Academy saw setbacks on every side. Beleaguered by the blacklist, they faced the double-bind of television’s creeping advance and the Supreme Court’s 1948 decision (United States v. Paramount, Inc.) dispossessing studios of their cinema chains. Like a swift slash of the guillotine, the Big Five lost their ability to block book and blind bid overnight. A breakup of monopolistic power that’s positively Pollyanna to our ears.

It’s barely a week since Being Frank With Melania dropped, and every day brings chillers of Donald “Gladys Knight” Trump and his pips, Bezos, Musk and Zuckerberg, consolidating autocracy through the blurring of corporate and state interests. The fascism freshly repressed at the time I am speaking of now! How heartening that, seventy-seven years ago, antitrust laws safeguarded competition and consumer choice. Après tout, even Barbra Streisand’s basement mall has become an Amazon “fulfillment centre”. A phrase every bit as terrifying as the one dangling over concentration camp gates; or the portentous “God is good, God is just” placards for peccant poorhouse paupers.

Capitalists claimed the Supreme Court’s ruling put the Mayers and Zanucks in a perilous position. How might they maximise their films’ “audience” now? (A word which here means “profits”.) Everything old is new again. Of this year’s Best Picture nominees, proving that anything but Dune: Part Two and Wicked: Part 1.5 made ten cents requires creative accounting that would elude Bialystock and Bloom. By 1955, the verdict, coupled with the new telly-box (and the patchy success of Cinemascope and similar novelties in luring viewers away from it) brought a slump in the movie business – and, by extension, the Academy’s fortunes.

Hardly surprising when you consider it was founded in 1927 as a union-busting exercise!

Although the awards had been shown on television twice before, anxieties around the medium held sway. Like the coronation of Elizabeth II, the small screen demystified the stars as it had the young queen. It made them human and more accessible, but also loosened the grip they, and their spin doctors, held on their image. A single gaffe could puncture even the most carefully-curated persona from newsreels and press releases.

Television was almost always transmitted in real-time. So technologically primitive that Desi Arnaz famously insisted I Love Lucy, unlike the earliest sitcoms, be shot on film in Hollywood; rather than kinescope (or “video”) in New York. A crude process whereby the camera was pointed at a monitor during a live East Coast broadcast in the hopes viewers on the West would receive anything but flickering white static. Whichever way you squared it, the aesthetics of rudimentary TV were laughably deficient to Academy bigwigs. To say nothing of the distaste in which commercialising the gala was held.

It’s second-nature for us to expect Glenn Close and Tina Fey expounding on the merits of Booking.com and Cardi B offloading Pepsi (heavens, what would Joan think?) at Superbowl Halftime or during lulls in the Oscars. But such a thought would have, and indeed did, send Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons into fits of convulsions. Nonetheless, the financial difficulties facing the Academy, precarious to this day, necessitated it.

True, the awards weren’t brought to audiences in 1955 by cigarettes or toothpaste or Kraft macaroni. Nothing quite so mortifying; it was the Oldsmobile Division of General Motors. Who insisted on one proviso. That a second Oscar telecast, in which the nominations for the preceding year were announced live, aired in mid-February. This show would earn $50,000 for the Academy coffers; along with $216,666 for March’s Main Event.

Nowadays, the Oscar nominations are issued at five-thirty a.m. Pacific Time. In 1955, NBC and Oldsmobile ensured they were announced at a more sensible hour of six in the evening. 9:00 p.m. New York. In lieu of Bowen Yang, another distinguished-looking thirty-four-year-old emceed: Jack Webb, Artie Green in Sunset Boulevard, soon to receive his greatest fame in Dragnet. The part of “Rachel Sennott” was played by Greer Garson.

One has to admire the event for its plucky innovation. Chancing their arms on ur-technology that likely wasn’t up to the task; not only did Webb and Garson present from NBC Burbank, the Academy transmitted portions of the show from three satellite locations. At the Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel, Irene Dunne and Lolly Parsons held court. At Ciro’s nightclub, proceedings were overseen by Humphrey Bogart and Photoplay’s Ann Higginbotham. At Romanoff’s, the sitting Best Supporting Actress winner, Donna Reed, hosted with gossip columnist Sheilah Graham. It was here that Joan Crawford, three months away from her marriage to the soft drink king Al Steele, arrived on the arm of “Prince” Michael Romanoff, the owner. No deposed Russian royal, he was the erstwhile Hershel Geguzin, a pants-presser-turned-con man from Brooklyn.

The reason a subsidiary Oscar telecast never caught on quickly becomes clear. NBC and its sponsor needed celebrity wattage. And, make no mistake, the Academy obliged: inviting approximately thirty of the most likely contenders to fill the four acting categories. Could you imagine them attempting such a stunt now? The tooth-pulling it would engender! Although there were a few no-shows, most accepted. It was a more naïve time, naturally, but there’s no denying ten left sorely disappointed.

Joan Crawford, overlooked for Johnny Guitar, puckered up to perennial nominee Walt Disney. He scored three nods. Six, according to contemporary reports who never ceded below-the-line nominations (in this case, for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea) to technicians; but to the studios responsible. Safely ensconced at Romanoff’s restaurant, Joan was spared the indignity of being photographed with a moon-sized Judy Garland at “Club NBC”.

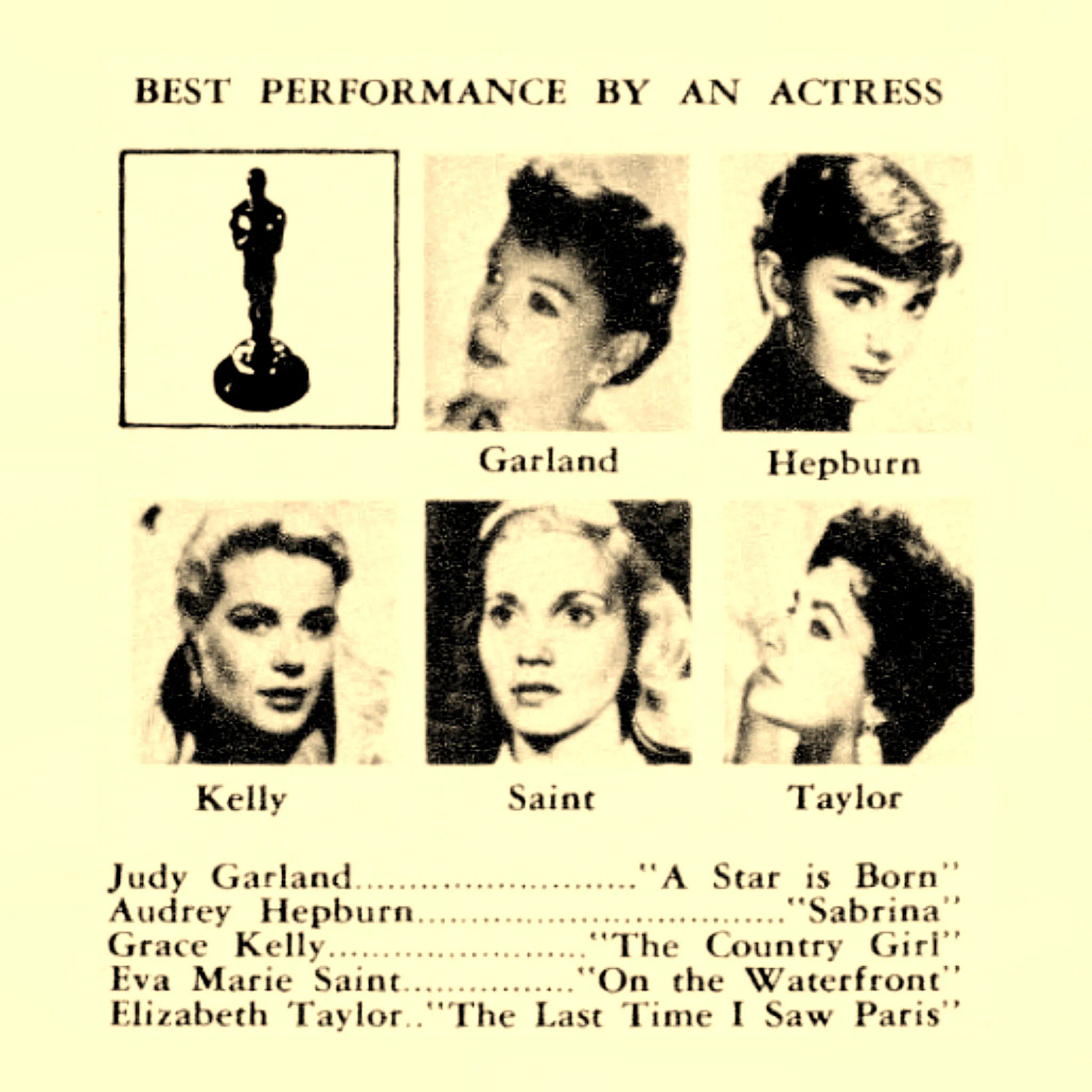

Judy was aptly recognised for her tour-de-force in A Star is Born, as was Jane Wyman in Magnificent Obsession, both lush remakes. Carmen Jones’s Dorothy Dandridge made herstory as the first African American Best Actress nominee, while reigning champ Audrey Hepburn secured the afterglow spot for Sabrina. Nothing for poor June Allyson. “The Girl with the Million Dollar Laryngitis”, as Van Johnson christened her, had given ‘em her timid-but-loyal-wife routine in three hits: The Glenn Miller Story, a bona fide smash, and two sleepers: Woman’s World and Executive Suite. Sadly, it took her role as a 1980s adult diaper spokeswoman for Junie to make her greatest contribution to popular culture. Was she considered a major star? Depends!

Almost as heavily pregnant as she was overdue, Ms. Garland’s Oscar dreams ended in tragedy six weeks later. Grace Kelly put on a cardigan and jam jar spectacles in The Country Girl. A feat of such theatrical derring-do, it made her Queen, no Princess Consort, of the Actors’ Studio.

Although ratings were respectable, and the Academy were certainly content with shekels in the kitty, the Old Guard grumbled. It was an affront to Academy prestige, they pleaded, for their broadcasts to be interrupted by station wagon advertisements. Critical response was dire. (“The video and film industries can stop worrying about competition,” the New York Times snickered “the only thing they have to fear is co-operation.”) Even so, they fired ahead with a 2nd Annual Academy Awards Nominations presentation in February 1956. But when fourteen out of twenty acting nominees were marked absent; “difficulties with the format” was cited as the reason to scrap it altogether.

A much less ambitious affair than its predecessor, the second – and last – nominations show occurred in a naked NBC soundstage. Fredric March and June Haver hosted, inviting the six nominees present to sign their names on a chalkboard à la What’s My Line?. Two leads: Susan Hayward and Ernest Borgnine; and four supporting players: Natalie Wood, Jack Lemmon, Arthur O’Connell and Marisa Pavan. When James Dean, killed in his car accident five months prior, was named a Best Actor contender for East of Eden, Ms. Haver’s voice trailed off. “May God rest his soul,” she eulogised “I would love to have the honour of writing his name on the board.”

Wisely, the press conference format we saw last week has been employed ever since.

For further information, I refer you to the exhaustingly extensive The Academy and the Award by Bruce Davis or, for bedtime reading, that old favourite: Mason Wiley and Damien Bona’s Inside Oscar.

Read Next:

More Oscar Highlights from the Archives:

Madam President: Inside Bette Davis’s Ill-Fated Tenure as Academy Pooh-Bah

It’s so interesting to think about how seeing stars on TV took away from their mystique. It really puts into perspective how commodified celebrities have always been. Thanks for the lessons in history and in Glenn Close.