What Happened ‘47

“...Miss Rosalind Russell, Mourning Becomes Electra, RKO Radio; and Miss Loretta Young, The Farmer’s Daughter, RKO Radio.” Presenter Fredric March cleared his throat.

Somewhere in the mezzanine, publicist Henry Rogers squirmed. He’d gambled the farm – or, at least, his wife’s plans for home renovation on this one. Having invented the “Oscar campaign” two years prior for Joan Crawford and 1945’s Mildred Pierce, and duplicating it for Olivia de Havilland in 1946; Rogers aimed to pull off a hat-trick. Everyone at the Shrine Auditorium agreed. Indeed, it was a foregone conclusion! “Rosalind Russell, then on to the after-parties.”

Best Actress was the final award of the night. An error the Academy replicated, two-and-a-half years ago, when anticipating the Widow Boseman’s Mrs. Norman Maine moment, they presented Best Picture before the leading categories.

“And the winner is R–…”

Rosalind Russell rose from her seat.

“Loretta Young, The Farmer’s Daughter.”

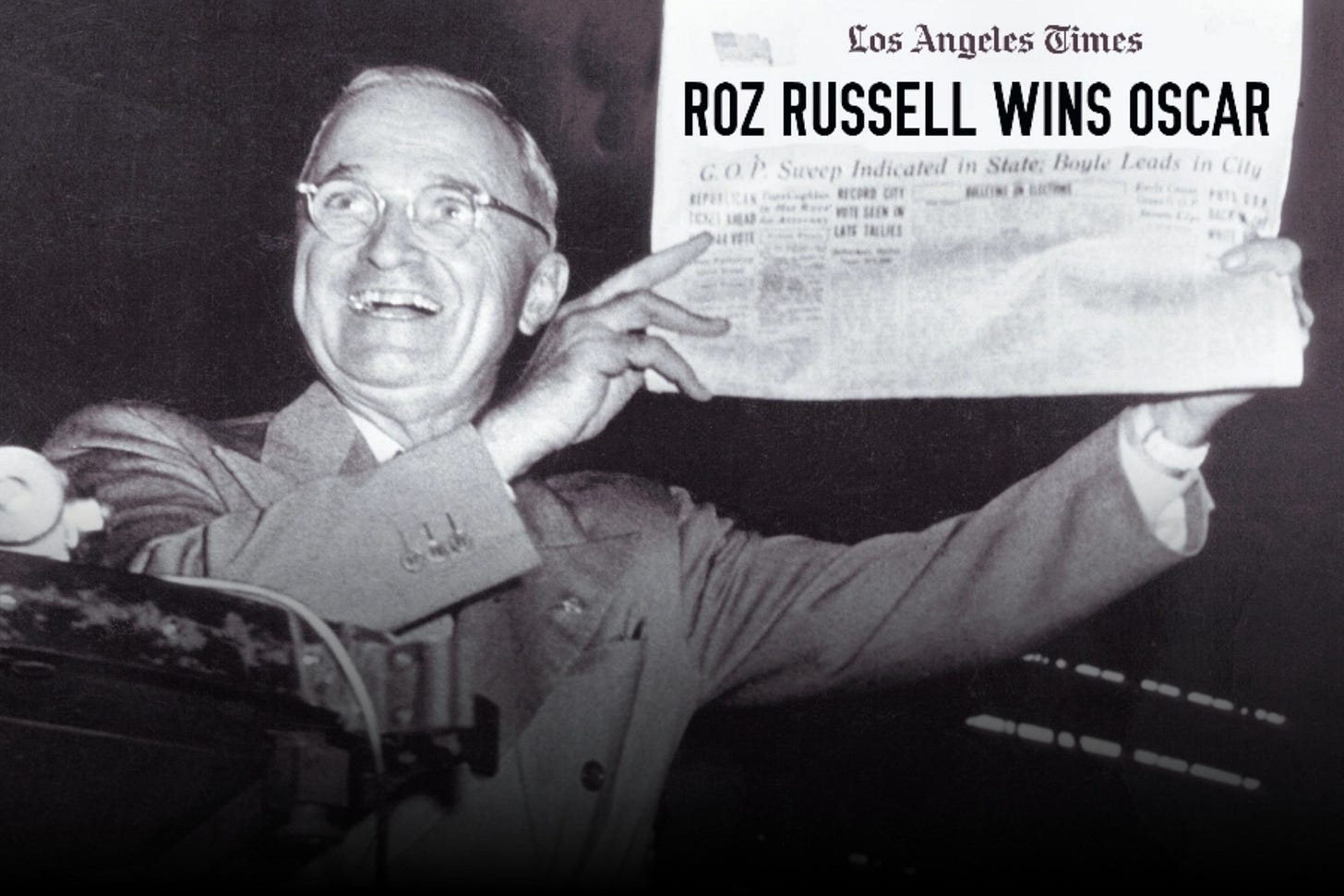

“Change those, and fast!”

At the Governors Ball, place settings labelled “Rosalind Russell” were swapped with “Loretta Young” ones faster than I squirelled the memes I had ready to go for Glenn’s 2019 triumph into the bowels of my Google Drive. When I saw that Our Number One Lady tempted fate by wearing gold, I quickly knocked off a parody of Hillary Clinton’s post-election elegy What Happened. Rosalind didn’t sport lamé – she was resplendent in white – but Loretta turned heads in Othiefia Stoleman green. “I dressed for the stage just in case,” Young deadpanned, as poor Roz led an unintentional standing ovation. In an eerie foreshadowing of the infamous “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline of eight months later, Henry Rogers caught a glimpse of the morning Times. “Roz Russell Wins Oscar.” Meanwhile, Mrs. Rogers was found vomiting in the toilet. (Freddie Brisson, the “Lizard of Roz”, had promised the Rogers’ a hefty bonus should his wife cross the line on her third nomination.) How would they pay for their living room now?

Narratives count! Admittedly, Mrs. Rosalind Russell Brisson, as a good Catholic lady was known, wasn’t quite an easy sell. Joan’s win had been the ultimate comeback, and Livvie’s owed more to the ‘de Havilland Decision’ of 1944 than her forgettable film. (Where Bette Davis failed, de Havilland bested Warner Brothers in court; curbing the contract system’s abuses – but that’s a story for another day.) Roz’s project, dubbed Mourning Becomes Rosalind Russell by wags, was even more of a turgid slog than To Each His Own. A bloated epic of three hours, it was RKO’s costliest flop. So much so that new Head of Production, Dore Schary, had no interest in being reminded of it. Flouting his predecessors’ foolhardiness, Schary promoted lighter fare. “Making pictures for the public, not the Academy.”

Pictures with a progressive attitude! Crowd-pleasing efforts like The Farmer’s Daughter – hokum, in which Loretta Young plays a Swedish maid-turned-Congresswoman – or The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer with Cary Grant. There was also The Bishop’s Wife, the Samuel Goldwyn-produced but RKO-distributed answer to It’s A Wonderful Life, uniting them. These were roles well within Loretta’s comfort zone, but proved she was an actress of substance with thirty years’ experience. After all, Ms. Young had started in silents aged four!

A studio copywriter, wary of the scorn in which overt Oscar begging was held, needed to “push the merch” without being too obvious. Films that attempted modern-style publicity generally received zilch. Like a “Eureka!” bubble o’er a cartoon character’s head, three magical words came to him. They struck just the right balance. “For Your Consideration.” The phrase wasn’t shamelessly thirsty; it simply suggested films the Academy might like to nominate. And why shouldn’t earnest Americana be included? The very first FYC ad appeared in the Hollywood Reporter in January 1948: “RKO respectfully submits the following efforts for your consideration…”. At a time when an Oscar revitalised diminishing box office returns, Mourning Becomes Electra was also recommended.

As we all know, it’s seldom the Best acting that wins. Usually, it’s the Most. And that, in addition to her overdue status, was what would carry Rosalind Russell to the Shrine Auditorium stage. Or so Henry Rogers thought.

In a field where Deborah Kerr, the external standout for Black Narcissus, was missing; Roz had the most compelling narrative among her rivals. With the exception of Loretta Young, all of whom were in social issue films. Joan Crawford battled mental illness in Possessed; Susan Hayward, domestic violence in Smash-Up; and Dorothy McGuire, anti-Semitism in Gentlemen’s Agreement. Young was an afterthought! Variety’s unfailingly accurate straw poll had her in fourth place and, to show her inconsequence, printed that she was nominated for The Bishop’s Wife. (Herstory never repeats itself, but it does rhyme. In 2001, Variety’s Army Archerd dubbed the unlikely Best Supporting Actress winner at 12-1, mother of all those queer children, as ‘Marcia May Harden’.)

In the preceding seasons, Mr. Rogers kept Crawford and de Havilland’s names in the papers from the last day of shooting through to Oscar night. In fact, Rogers masterminded the idea of Joan, miraculously cured from “sudden illness”, accepting her prize at home. Given the exposure it got, one would be forgiven for thinking the awards were held in Joan Crawford’s bedroom. For Roz, he organised “Rosalind Russell Fan Clubs” up and down the country. He had a Beverly Hills Parent-Teacher Association name her “Actress of the Year” and a USC fraternity, “Outstanding Actress of the Twentieth Century”. The Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Drama (although there wasn’t a corresponding Comedy category until 1950) was claimed by his client. He even convinced a Las Vegas casino to offer bets on the race, with Roz as the dead-on favourite.

Travis Banton, overseer of Marlene Dietrich’s costumes at Paramount, designed her victory gown. Adrian, who fulfilled the same function for Garbo at MGM, dressed Loretta. Banton, a gay man and a drunk (and in Hollywood’s mind, those “weaknesses” were conflated) hoped Roz’s look would bring renewed interest in his career. Banton understood the precarity of the freelancer. His home studio had dismissed him on account of his weaknesses, nine years earlier, at the behest of an upstart assistant: a certain Edith Head. Like Metro’s Adrian, Banton’s heyday predated a dedicated Oscar for costumiers. When that category was instituted in 1949, his deceptive disciple Ms. Head won no fewer than eight – a record in her field! Banton died in 1958, beholden to the bottle. “Poor Travis,” Roz said, seeing her designer dissolve into tears when Loretta Young’s name was called, “I feel so sorry for him”. “We’re going to the party afterward anyway,” she consoled “I won’t be bitter”.

The following year, Jane Wyman, another doyenne of Christian charities (although, like Roz, I imagine she knew the truth about Loretta’s “adopted” daughter) enlisted Henry Rogers’s help. In Johnny Belinda, she played a deaf-mute – but the publicist, still smarting from the ‘47 fiasco, reckoned “Most Acting” alone wouldn’t carry her. The sympathy vote was her calling card. Wyman had lost a baby and was in the midst of a divorce, leading Ronald Reagan to quip: “I think I’ll name Johnny Belinda co-respondent”. Therefore, Rogers brought home three Best Actress Oscars in four years, discounting the Russell blip.

“Don’t say ‘poor Roz’,” Loretta Young pontificated “it was cruel for the polls to come out and say that she was going to win. She will go on to win an Academy Award and then some!”. (Naturally, beyond an honorary humanitarian award in 1973, Ms. Russell went to her grave unrecognised.) Roz was too classy to disparage her friend and fellow Catholic. She even agreed to be photographed with Loretta at the Governors Ball. The sole mention What Happened receives in Russell’s posthumous 1977 memoir is: “Half a loaf can feed you, but when you get the whole loaf, you know the difference”.

In the words of Glenn Robinette Close Jr., ain’t that the truth.