Hattie McDaniel’s Legacy (1939)

This week’s Substack explores the enduring influence of HATTIE MCDANIEL and the racial stereotypes and industry prejudices that both celebrated and constrained her.

Now! A warning! The eagle-eyed among you will note that this polemic comes from the archives. February 2023, to be exact. But before you nickname me “Sol E. Rooney”, I’m not pulling a fast one. Writing the same work twice and passing it off as an original. I’ve refined and toned down the, let’s face it, exclamatory style of my juvenilia.

I so enjoyed penning my Case for IBS, the other day, that I thought we’d revisit renowned Supporting Actress contests in the coming weeks. However, I felt that beginning with my next subject would open “in media res”.

I hope Hattie McDaniel’s Legacy serves as an unofficial prequel.

FADE IN:

THE COCOANUT GROVE AT THE AMBASSADOR HOTEL — LOS ANGELES, FEBRUARY 29TH 1940 — EVENING

FAY BAINTER strides onstage.

She’s bestowing the night’s penultimate Oscars. Best Supporting Actor and Actress.

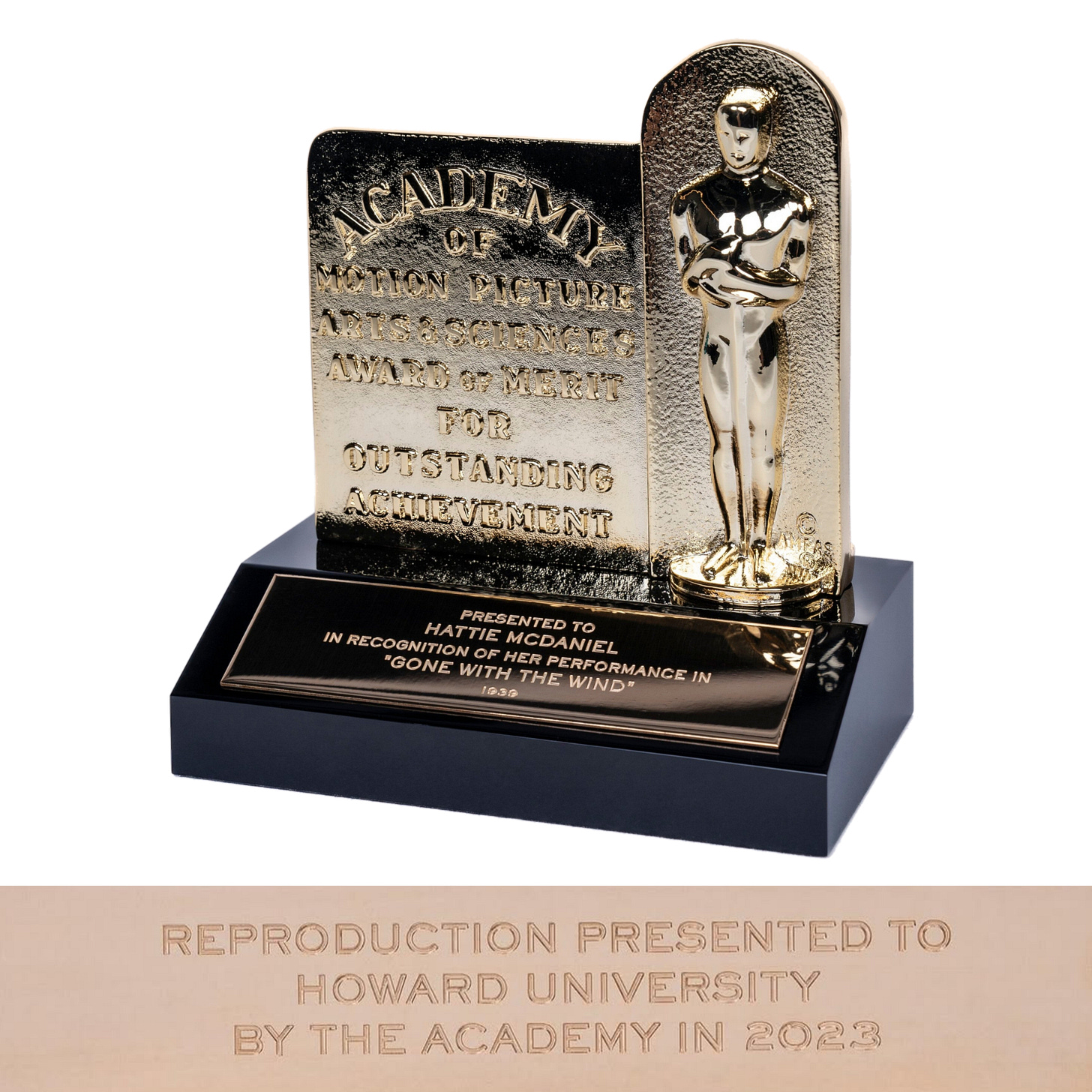

To show the lowliness of the prizes, Bainter brandishes plaques rather than full-sized statuettes. In the Academy’s twelve-year history, these awards have only been awarded thrice. But unlike technicians similarly honoured with these lesser trophies, supporting winners are allowed to say a few words.

THOMAS MITCHELL, recipient for “Stagecoach” (but equally for “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington”, “Only Angels Have Wings” and “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”; to say nothing of a certain cult film from Selznick International) manages eleven: “I didn’t think… I didn’t know I was quite that good!”

After Gerald O’Hara exits; the venerable character actress takes a deep breath.

FAY BAINTER

I’m really especially happy that I am chosen to present this particular plaque. To me, it seems more than just a plaque of gold. It opens the doors of this room, moves back the walls, and enables us to embrace the whole of America -- an America that we love, an America that almost alone in the world today, recognizes and pays tribute to those who give her their best, regardless of creed, race, or color. It is with the knowledge that this entire nation will stand and salute the presentation of this plaque, that I present the Academy Award for the best performance of an actress in a supporting role during 1939 to Hattie McDaniel.

Archaic attitudes aside, I know you’re very fond of Gone With the Wind. It’s our gateway drug to Old Hollywood. But, let’s face it, the second half drags. With one exception. The moment when Hattie McDaniel’s Mammy and Olivia de Havilland’s Melanie mourn on the staircase. Shot in one long take, everyone on the lot agreed. It would bring McDaniel laurels.

“That scene probably won Hattie her Oscar,” Dame Olivia confessed “and that broke my heart – at least at the time.” De Havilland felt she missed out not because McDaniel was superior, but because the Academy wouldn’t give their fledgling supporting prize to a star (as opposed to the journeymen players for whom it was intended).

Five years earlier, in the absence of this category, a storm erupted when Louise Beavers wasn’t nominated for Imitation of Life. Although only thirty-two and a year older than her on-screen daughter, “the tragic mulatto” Fredi Washington (roles played by Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner in the more famous remake), Beavers embodied the “Mammy” archetype. The sexless, shapeless African-American domestic, whose sole purpose was to magnify the appeal of her white employer. Columnist Jimmie Fiddler wrote: “I lament that the motion picture industry has not set aside racial prejudice in naming actresses. I don’t see how it is possible to overlook the magnificent portrayal of Louise Beavers in Imitation of Life”.

Like McDaniel, Beavers became a controversial figure. For taking the only roles open to her. As the former quipped: “I’d rather play a maid and make $700 a week than be one for $7”. Yet she also brought pathos and dignity to a caricature. “Any actress who can steal a picture from Claudette Colbert,” Fiddler continued “will be given few chances to steal from others.” Foreshadowing McDaniel’s post-Gone With the Wind career, Beavers, despite a flurry of adulation, stayed stuck in thankless parts. Always a servant or slave – and often not credited at all.

It would take half a century for another African-American actress to win an Oscar. Whoopi Goldberg for 1990’s Ghost. In many respects, a make-up for her loss for The Color Purple. In 1948, the Academy avoided embarrassment by giving James Baskett, Uncle Remus in Disney’s notorious Song of the South, also starring McDaniel, an honorary award. Sidney Poitier didn’t win for playing an upstanding doctor or lawyer, but the hustler in Lilies of the Field. Lena Horne saw her talent confined to musical cameos, as tailor-made roles in Show Boat and Pinky went to (the white) Ava Gardner and Jeanne Crain. Dorothy Dandridge, cited for 1954’s Carmen Jones, died penniless a decade later.

Of the thirteen black women to earn a Best Actress nomination (including the lone winner, Halle Berry, twenty-three years ago), the majority are for films depicting poverty. Indeed, both times two black actresses were nominated in the same year (Diana Ross and Cicely Tyson in 1972 and Viola Davis and Andra Day in 2020), one of them played the doomed Billie Holiday. The statistics for Supporting Actresses are only marginally better. And Hattie McDaniel?

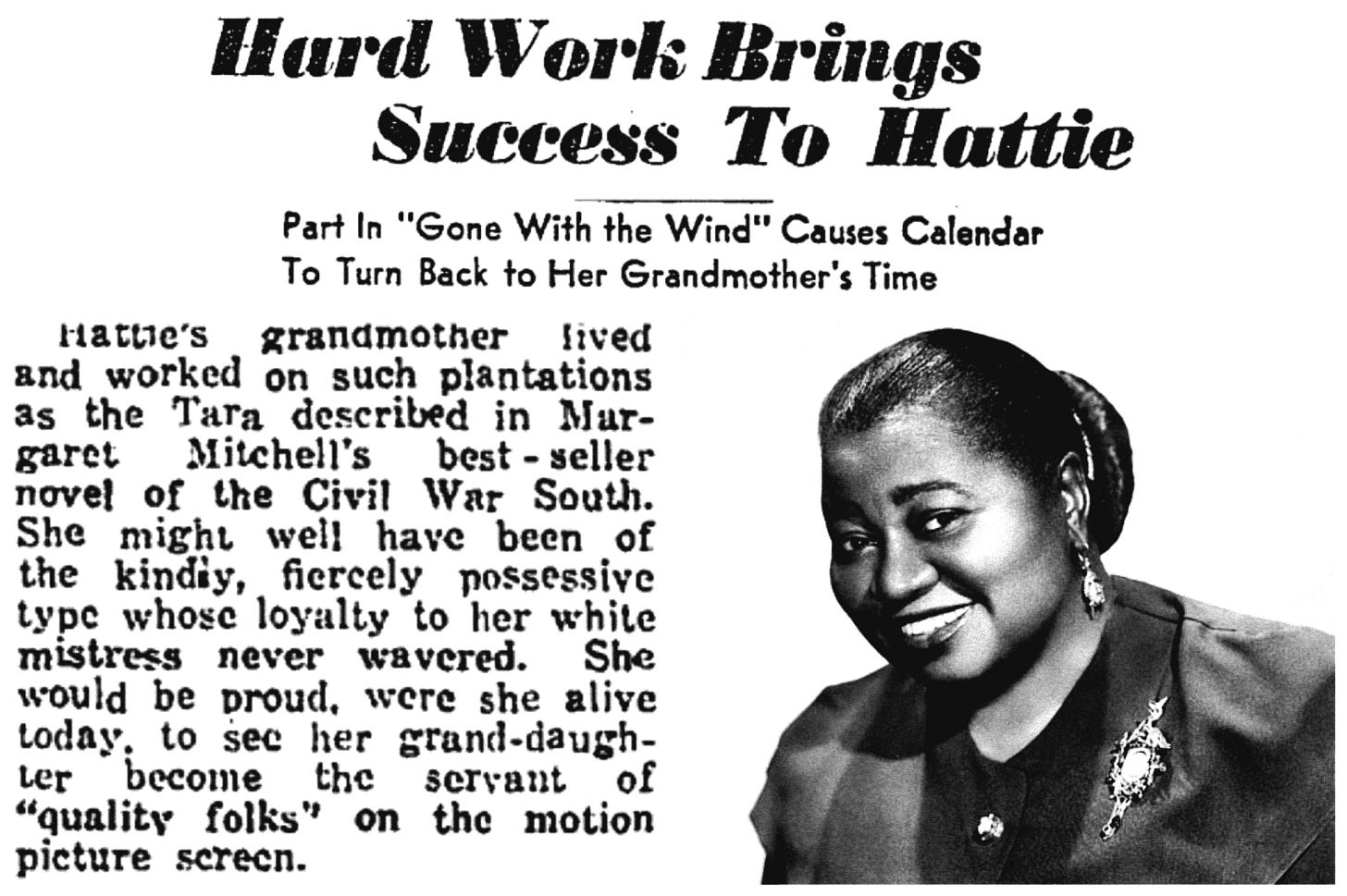

It seems she was remembered, at least initially, as Mammy – not the actress who played her. There are more references to “Mammy McDaniel” in the various biographies I consulted than you can shake a stick at! Furthermore, her Oscar became a way for Hollywood to pat itself on the back. A chance to say: “Look how liberal and broad-minded we are!”. Little has changed. In 2006, George Clooney praised the Academy for the optics of this choice “when blacks were still sitting in the backs of theatres”.

And Hattie McDaniel in the back of the room!

The Ambassador Hotel operated a strict segregation policy, but Ms. McDaniel was admitted as a personal favour to David O. Selznick. On Oscar night, she was seated at an obscure table and refused entry to the “No Colored” after-party. As the winners were leaked beforehand – Olivia de Havilland was found sobbing in the kitchens – the studio prepared Hattie’s remarks. “Not only was she the first of her race to receive an award,” Variety gushed “she was also the first Negro to ever sit at an Academy banquet”, before cruelly noting: “in addition to her ability as an actress, McDaniel could pose as an ad for Aunt Jemima.” (The popular line of breakfast pancakes and syrups, tactfully rebranded as the Pearl Milling Company in 2021.)

Rather than capitalising on her Oscar, moguls thought “Mammy” was Hattie’s unique selling point. This was Jack Warner’s view when he used her in two Bette Davis weepies, The Great Lie and In This Our Life. Contemporary gossip rags invented stories of Davis having Hattie’s scenes cut, so eager was Ms. McDaniel for a second gong. Codswallop! (She got pitiful billing, too.) White women wrote Selznick in droves, looking for “Mammy’s recipes” – the only area in which they’d seek a black woman’s expertise. Although disdainful, McDaniel eventually submitted instructions for corn bread, collard greens and “Mammy’s Fried Chicken”.

Hattie McDaniel navigated the treacherous waters of racial stereotypes; balancing criticism from her community with grace and dignity. While the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had the worst racial epithets from Gone With the Wind removed, McDaniel warned co-star Butterfly McQueen who refused to eat watermelon on camera or let Vivien Leigh slap her: “You’ll never come back to Hollywood, you complain too much”.

As Mammy, she transcends comic relief. She is the backbone of that picture and the reason it endures. “I wanted to turn this stock role into a living, breathing character,” she articulated “I portray the type of Negro woman who worked honestly and proudly.” Her Oscar speech may seem dated by today’s standards, but it came from the heart. Abandoning the words Selznick approved, McDaniel and her friend, the black writer Ruby Berkley Goodwin, came up with this salutation:

HATTIE MCDANIEL

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, fellow members of the motion picture industry and honored guests. This is one of the happiest moments of my life, and I want to thank each one of you who had a part in selecting me for one of the awards, for your kindness. It has made me feel very, very humble; and I shall always hold it as a beacon for anything that I may be able to do in the future. I sincerely hope I shall always be a credit to my race and to the motion picture industry. My heart is too full to tell you just how I feel, and may I say thank you and God bless you.

Fostering a commitment to education and empowerment, Ms. McDaniel bequeathed her Oscar to the historically black college Howard University in 1951. A year later on October 26th 1952, seven months shy of her sixtieth birthday, she succumbed to breast cancer. And the award? Within two decades, it vanished! Simply misplaced, some said. Others claimed it got lost during the chaos of ‘68. Yet more theorised that radicals, wishing to make a statement about McDaniel’s roles as a white man’s “Uncle Tom”, hurled it into the Potomac.

Like Maleficent’s minions spending sixteen years searching for a baby, Bruce Davis in The Academy and the Award suggests location efforts were hindered by a focus on finding an Oscar statue; not a plaque. Supporting actors had been promoted to the little bald man in 1943 – albeit an ersatz one – which could be traded for the genuine article once wartime metal shortages subsided. In 1946, the Academy extended this exchange programme to include all winners of a pre-war plaque. Several got a double upgrade: from plaque to statue, and from plasticine to metal. At the recipient’s own expense, mind you. But many, like McDaniel, fond of their original trophies, never made the change.

Hattie McDaniel’s legacy reflects a woman who excelled despite enormous challenges. While the NAACP may have charged her with abandoning her race, she pried open doors that had previously been shut. Her generosity was legendary! She served as the chairwoman of the “Negro Division” (the terminology of the day) of the Hollywood Victory Committee during World War II and helped organise scholarships. When neighbours tried to evict her and other African-American homeowners, specifying deeds that made their Los Angeles district “white only”, she took them to court and won.

Without Hattie McDaniel, there wouldn’t be a Da’Vine Joy Randolph, a Regina King, an Octavia Spencer or a Mo’Nique; something the latter acknowledged in her own Oscar speech. Indeed, her outfit was identical: a blue gown and white gardenias.

Above all, Hattie McDaniel was a credit to herself.

INT. CRAMTON AUDITORIUM, HOWARD UNIVERSITY — WASHINGTON, D.C, OCTOBER 1ST 2023 — EVENING

PHYLICIA RASHĀD strides onstage.

She’s the night’s final speaker. It’s a special event in Ms. McDaniel’s honour.

Industry heads, scholars, journalists and members of Hattie’s family have just reflected on her legacy. Not only the historic Academy first, but her career as a comedienne, singer-songwriter and pioneering radio star.

The first Oscar-winner of colour on a US postage stamp. An inductee into both the Black Filmmakers and Colorado Women’s Halls of Fame. The recipient of TWO stars on Hollywood and Vine.

She made 300 films, but was credited in barely a third of them.

Rashād takes a deep breath:

PHYLICIA RASHĀD

When I was a student in the College of Fine Arts at Howard University, in what was then called the Department of Drama, I would often sit and gaze in wonder at the Academy Award that had been presented to Ms. Hattie McDaniel, which she had gifted to the College of Fine Arts. I am overjoyed that this Academy Award is returning to what is now the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Arts at Howard University. This immense piece of history will be back in the College of Fine Arts for our students to draw inspiration from. Ms. Hattie is coming home!

Ms. Rashād, the dean of the school, brandishes a curious sculpture. An exact replica of the plaque Hattie McDaniel received in February 1940.

FADE OUT.

Read Next:

The Case for IBS: Why Isabella Rossellini Should Win Best Supporting Actress (but Probably Won’t)

Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the (Revolution in France) Oscar Nominations, 1955