Hagen Daze (1952)

This week’s Substack delves into the life of JEAN HAGEN whose professional brilliance was overshadowed by personal turmoil, but whose legacy shines brightly.

Jean Hagen was twenty-eight in Singin’ in the Rain which is somehow deeply distressing.

I know what you’re thinking. Better pull up those socks, Mark! You only have “twelve” – oh, shut up! – more years to deliver a performance as indelible as hers as Lina Lamont.

Our Number One Lady, the GC, was thirty-five before she made a talkie, vous savez. “A late bloomer who barely survived an early frost”, People magazine called her. Oh, for that adage to hold true for Mr. Mark O’Donovan. An optimistic fallacy and a naïve one. As though she came from the tenements like me! Glennie was a Connecticut surgeon’s daughter. She hails from the most aristocratic background America can offer. With her as its Princess Royal. The descendant of colonial gentry; and kin to Marjorie Merriweather Post, chatelaine of Mar-a-Lago.

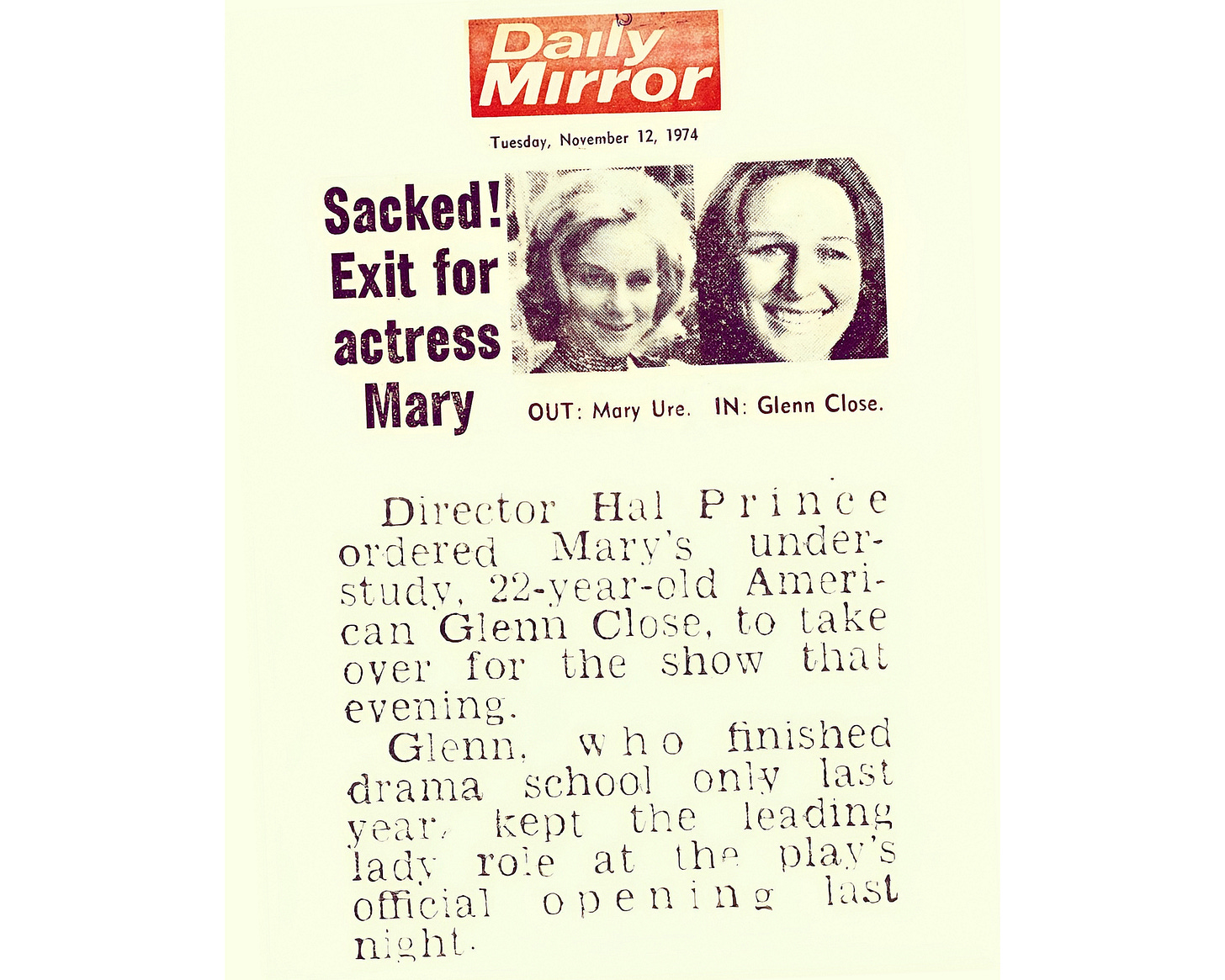

By Close’s Calendar, I should be replacing the alcoholic lead of a Restoration comedy on Broadway about now. Glenn’s first job as a mature graduate from the College of William & Mary? A hand jo– no. No, it was understudying Mary “I’m not sick, I’m not drunk, and I’m not late” Ure in a Hal Prince production of Congreve’s Love for Love. Like Shirley MacLaine, Ms. Close seized the spotlight at the eleventh hour. When, between matinée and evening shows, the star withdrew. Unlike Carol Haney’s ankle, for a heart-wrenching reason. The director reached his limit with Ms. Ure’s inebriated difficulty recalling lines.

In a gesture of exceptional decency, the latter left this note.

It is a tradition in the English theatre for one leading lady to welcome the next leading lady into her dressing room. I learned this when I was very young and making my debut at the Haymarket. I was surprised to find a letter for me from Dame Peggy Ashcroft, who had just closed after a long run. I salute you and welcome you. Be brave and strong. Mary Ure.

In November 1974, Ms. Close started as a thirty-ish glenngénue. The following April, after accidentally imbibing a lethal cocktail of booze and sleeping pills, Mary Ure was dead. She was forty-two.

It’s Best Supporting Actress Month, this month, on O,SU!.

Which begs the question: is there a greater injustice than Jean Hagen not winning in 1952? (Failing Dame Angela’s loss for The Manchurian Candidate, a decade later.) Gloria Grahame, stalwart figure though she was – and I urge you to watch Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool (2017) where Our Number Two Lady Annette offers a Lesbian Film Critics’ Award-worthy portrayal of her final years – is the category’s weakest victor. Indeed, the embarrassment surrounding her win is cushioned only by The Greatest Show on Earth (in which Grahame also starred) foiling High Noon and The Quiet Man for Best Picture. Singin’ in the Rain wasn’t even nominated.

Singin’ in the Rain is one of the finest movies ever made. Certainly the finest musical. And while I could rhapsodise on its technical wizardry or set pieces (Donald O’Connor’s “Make ‘Em Laugh”, the dream ballet with Cyd Charisse, Gene Kelly’s mythic title number where lighting and camera trickery – not milk! – simulated precipitation), I chiefly remember it for Jean Hagen. And her vocally challenged screen siren, Lina Lamont.

Much like balding gracefully or empathy, we’ve forgotten the definition of a supporting turn. Hagen’s is the prototype. As with all buffoons, she appeals to everyone: from the smallest child to the most esteemed scholar. Each Christmas and Easter, when Singin’ in the Rain aired on Telly Éireann, I wasn’t captivated by the intricacies of three-strip Technicolor – but this garish, shrill-voiced, clown-woman who breaks your heart.

In lesser hands (it was initially assigned to Nina Foch, who specialised in haughty sophisticates), Lina Lamont would’ve been a one-dimensional villain. Not Jean Hagen. She makes the downfall of a fraudulent silent star side-splittingly funny and poignant. Her soundbites and shibboleths live in my head mortgage-free. (Well, hope springs eternal…) “What do you think I am? Dumb or something?”; “Well, I caaahn’t make love to a bush!” and “Why, I make more money than Calvin Coolidge! Put together!”. (You read those in her voice, didn’t you?) How about: “People? I ain’t people! I am a ‘shimmering, glowing star in the cinema firm-a-mint!’”. It’s no coincidence that her lines are the picture’s most quoted.

Notwithstanding its myriad appearances on Sight and Sound’s Greatest Films list, co-director Stanley Donen called Singin’ in the Rain “very creaky”. “There are about four good things in it,” a self-effacing Donen carped, “Donald O’Connor’s “Fit as a Fiddle”; “Make ‘Em Laugh”; Gene’s “Singin’ in the Rain”; and one hilarious sequence when they’re recording sound for the first time. But there are no characters! Except for Jean Hagen.”

Beyond her performance, Singin’ in the Rain was snubbed at the Academy Awards. It scraped by with one measly nomination. Best Scoring of a Musical Picture. It didn’t land that Oscar; nor did it take the Golden Globe for Best Picture Musical/Comedy. Those went to With a Song in My Heart, a Susan Hayward weepie about Jane Froman’s 1943 aviation incident. Plane crashes proved rather a jinx for Kelly and Donen’s masterpiece. After a paltry nine minutes on screen, Gloria Grahame is dispatched in one in The Bad and the Beautiful.

Academy oversights are seldom seen as such in their time. Ms. Grahame didn’t win in a shocking upset. Her selection was justified by the era’s standards. Variety correctly predicted she’d prevail on cumulative impact. She starred in three hits in 1952! Gloria was primed for awards glory; the only question was for which turn. As Angel the Elephant Girl in Greatest Show? She secured that job after Lucille Ball got pregnant. (“Congratulations, Mr. Arnaz,” huffed an exasperated C.B. De Mille, “you’re the only man who has ever screwed his wife, Cecil B. De Mille, Paramount Pictures, and Harry Cohn, all at the same time!”) There was Sudden Fear with Joan Crawford and Jack Palance at RKO. But it was MGM’s all-star The Bad and the Beautiful for which she succeeded.

Let’s face it, my Substacks follow a well-tread formula. With barely-disguised projection about my own feelings of inadequacy, I highlight the hardship of a historical homo or harridan. Usually, a great star. (S)he either succumbs to her ordeal (and there’s always an ordeal) – or triumphs. Only for their dazzling success to be short-lived.

Today’s article is no exception. And, frankly, any of the ladies I’ve been edging you with could suffice. (Even Mary Ure was a Supporting nominee for 1960’s Sons and Lovers, after Warren Beatty advised Joan Collins to turn it down. Much like testing for Cleopatra or Marilyn warning her about wolves, it’s not something Elizabeth Tinker brings up. Except on days of the week ending in ‘Y’.)

Jean Shirley Verhagen was born in Chicago on August 3rd 1923. Perhaps, it was Protestant work ethic – or making good on her white-collar father’s frustrated opera dreams – but for thirty years, she tackled radio, Broadway and Hollywood with ambitious abandon. After coming down from Northwestern in 1945, she married actor-agent Tom Seidel and bore two children. Son Aric Phillip (“they wanted something that would look good on a marquee”) and daughter Christine Patricia – named for Hagen’s closest confidante, Patricia Neal. “Both my parents were very driven, strong people,” Aric Seidel confessed, “they knew exactly what they wanted. In retrospect, it reminds one of the old saying: watch out what you wish for.”

Like a hardboiled Damon Runyon broad, Jean shot straight. While ushering at the Booth Theatre in 1946, she made wisecracks about the play – in front of its authors. Charles MacArthur was so impressed by the girl’s moxie that he immediately cast her! And implored her to drop the “Ver-” from her patronymic. Pat Neal, with whom she lodged in cockroach-infested walk-ups, “always liked her real name much better”. (Around this time, the other half-Dutch soubrette, who’d later compete with Jean for her most famous role, changed hers from “Nina Fock” to “Nina Foch” for obvious reasons.) The following year, Jean landed a gig as Judy Holliday’s understudy, and later vacation replacement, in Born Yesterday. It was the first of many comparisons between them.

They went to California together. Two New York hoofers, adding lustre to Cukor’s courtroom caper Adam’s Rib. Leads Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy famously allowed crucial scenes to be shot from the perspective of Holliday’s persecuted wife. Their hope was that this could serve as Judy’s unofficial screentest for the film of Born Yesterday. Hagen, playing the floozy, received no special treatment. The gambit worked. Judy Holliday reprised her role; won an Oscar; and, despite her genius-level IQ and rarefied social conscience, was lumped with variations on Billie Dawn thereafter. Nonetheless, by the time Singin’ in the Rain came up, written by her Greenwich Village confrères Betty Comden and Adolph Green, she was too big a star to take a supporting part. Enter Jean Hagen.

In many ways, Hagen’s movie career was an inverse of Holliday’s. While Judy was typecast as the “dumb blonde”, Jean’s best bimbos are an exception. Watch any other performance, and you’ll see what a deviation Lina Lamont was from her wheelhouse. True, Hollywood had no idea what to do with this angular brunette – who, in reality, spoke in mellifluous tones and sang beautifully. (In the sound booth scenes in Singin’ in the Rain, it’s actually Jean Hagen dubbing Debbie Reynolds dubbing Jean Hagen!) But, confined to housewives and drudges and the occasional “problem woman”, her talents went untapped. “Every time Mr. Mayer would get mad at me,” Hagen lamented, “he’d punish me by putting me in a Lana Turner movie.”

1950 brought a rare opportunity to flex her acting chops. The Asphalt Jungle for director John Huston. Hagen plays Doll Conovan, a simping would-be gangster’s moll. (Good grief, that’s probably what they would’ve made my name at MGM. “Hedda Hopper Scoops! Irish Heartthrob Doll Conovan, 22 [sic], Spotted With Starlet Nancy Davis at Brown Derby; Rumored to Top Rock Hudson… for 1951’s Most Eligible Bachelor.” No.)

Kathleen Freeman, who played Lina Lamont’s diction coach, said: “Jean Hagen was never appreciated for her capabilities. If you see her in Singin’ in the Rain and you see her in The Asphalt Jungle, most people didn’t know it was the same person. That’s pretty good work. She was extraordinary, and a good friend. And beautiful – good Lord almighty, she was a pretty thing”. Donald O’Connor added: “She was a consummate actress. She was the sweetest gal in the world but she was on the quiet side, not like Lina Lamont at all. No, she was a straight, legit actress. They didn’t get a ditzy blonde to play the part, they got a great actress to play the ditzy blonde. That’s why that part is so dynamic and so wonderful”. To John Huston, “she had a wistful, down-to-earth quality rare on the screen”.

Doll Conovan should’ve unlocked opportunities. For Hagen, the doors stayed shut. “There were only two girl roles [in The Asphalt Jungle],” she sighed, “and I obviously wasn’t Marilyn Monroe.”

“Jean started out with a bang at MGM,” Patricia Neal writes in her 1988 autobiography As I Am “but Hollywood left her nursing hopes of fulfilment, and when the teat dried up, she started on the bottle.” “Tom was a big drinker,” Neal continues “and Jean kept up. It’s terrible how much they drank. She became an alcoholic but I don’t think Tommy did. You know, the story of Days of Wine and Roses? That was Jean. He drank and she drank, but she suffered and he really didn’t.”

Neal recalls one particularly embarrassing episode when she and actress Mildred Dunnock accepted Jean’s invitation to lunch. “When we arrived, we found a wreck of a human being. She was completely smashed. Nothing had been prepared and the house was a mess, dirty dishes stacked in the sink. Millie and I washed them and straightened up a bit and left. I didn’t know what else to do. Jean never liked people meddling in her affairs. Eventually Tom left her. My dear friend did finally quit drinking, but there were many heartbreaks to come.”

“I remember my father’s explanation of why he divorced my mother,” son Aric corroborated “he said he hoped to shock her out of drinking by way of the divorce. I know he felt very badly about it and he spent a couple of years “on the [psychiatrist’s] couch” trying to come to grips with the guilt.”

Seidel felt culpable when Jean left their luxurious Westwood residence for a modest flat and then the Motion Picture Home – in her forties – after losing custody of the children in 1965. His remorse intensified when Jean was found alone and unconscious, three years later. Emerging from the coma, Jean swore off alcohol forever. A diagnosis of throat cancer strengthened her resolve, leading her to additionally quit smoking. The Dutch Calvinist spirit dies hard.

“Acting is all I’ve wanted to do since I was a kid,” Hagen surmised, “I want more than anything else to work again – and with the help of God, I will.”

Regardless of their ongoing health battles and shared trauma, Patricia Neal was heartened to see her friend swiftly looking better than she had in years. Breaking her jump to source laetrile in Germany – snake oil notoriously used by Steve McQueen in his fight against mesothelioma – Neal and Hagen reunited in London. “Jean was bubbly and bright and so much the way I remembered her.”

A throwback to the old days when Hagen allowed Neal the use of the Seidels’ Manhattan apartment for her rendezvous with Gary Cooper. (“Pat thinks Gary is going to marry her,” Hagen confessed to a mutual friend, twenty-five years prior, “but he is not. Everybody in this town knows it but her. And Pat is not going to accept it.”) Jean always had Pat’s best interests at heart. When Gary Cooper publicly supported a member of the Hollywood Ten, Hagen beseeched her to “keep my trap shut before I got branded a Commie along with everything else!”.

By the 1970s, this wisdom remained sharp. When Felicity Crossland, a set designer with eyes on Pat’s husband Roald, arrived one day with gifts galore; Hagen remarked: “Isn’t she overdoing it?”. Her instincts were correct. The little parvenu was Felicity Dahl within a decade.

Below is Hagen’s final performance. A caustic landlady in Alexander: The Other Side of Dawn. It aired three months before her death in August 1977. Looking far older than her fifty-three years, her body ravaged by illness, her cut-glass voice a whimper; I felt doleful at this great star’s decline. Yet it adds a meta touch to what otherwise would be a forgettable TV movie: the story of a Hollywood hopeful-turned-rent boy. To me, this cameo is no tragic denouement – but a testament to enduring strength and character. And a reminder that time and tide wait for no man.

“She had a pretty miserable middle-age and it was such a sad end,” Jean’s daughter Christine Patricia eulogised “but she always had a really incredible attitude. She was such a great lady.” “Jean was clear at the end of her life,” her namesake, Patricia Neal, confirmed “and she was a good woman. I adored her.”

She brought a little joy into our humdrum lives. Which makes me feel as though her hard work ain’t been in vain for nothing.

Read Next in My Supporting Actress Series:

Hattie McDaniel’s Legacy (1939)

The Case for IBS: Why Isabella Rossellini Should Win (2024)

See Also:

Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the (Revolution in France) Oscar Nominations, 1955

glenngénue is Pulitzer worthy