When I was a child in the fourteenth century, I’d watch the trailer above on a perpetual loop. It was for George Lucas’s “special editions” of Star Wars, tucked away on some forgotten video cassette.

(“Asperger’s syndrome? Oh, that’s the buzzword now, is it? Right. Sure, you know everything, Mrs. O’Donovan. Look, Mark’s impossible. Why complicate things with labels? You’re just an overbearing mother. I’ll bet he’s got a telly or PlayStation in the bedroom, hasn’t he? And a mobile? Well, there you are. Now, if you’ll excuse me, my waiting room’s full outside. Patients with real problems.”)

“For an entire generation,” intoned a radio announcer’s voice, “people have experienced Star Wars the only way it’s been possible. On the TV screen.” Then, as John Williams swelled and a spaceship soared, “But if you’ve only seen it this way, you haven’t seen it at all!”.

Frankly, I can’t imagine a nicer format.

My Proustian ideal is the untouched Star Wars on a squat, square television. Fuzzy tracking lines, print grain, and “Han Shot First” intact. Preferably on a Sunday afternoon, a roast dinner – suet making its unwelcome appearance in both main course and sweet – congealing in my gut like turgid cement.

The latest controversy among the terminally online concerns another act of cinematic butchery. The outrage is familiar, but it makes Lucas’s alterations look benign. The same free market idiocy. The same race to the bottom.

It recalls early TV broadcasters who dismissed letterbox as wasted space and “innovated” with pan and scan. Cropping and zooming with abandon, they sacrificed half the frame – and all the director’s intent – in the process. A necessary evil, I grant you. Living rooms were spared the ordeal of squinting at bordered images. Most major productions after 1953, when The Robe introduced widescreen, would’ve appeared as a thin strip edged by black bars on television. Until the turn of the last century, apart from Laserdisc-owning anoraks (“There was none of that autism nonsense in my day!”), few people saw films properly at home.

One would be forgiven for thinking the chariot race in Ben-Hur featured two horses, not four, or that the musical numbers in Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and The Sound of Music were hazy close-ups of prairies or Alps. Three brides, three brothers, and three von Trapps at any given time. West Side Story became odd angles of empty streets in pre-glenntrification New York. The Busby Berkeley symmetry Gene Kelly and Michael Kidd aped in Hello, Dolly! shrank to scattered crowds; Omar Sharif’s entrance in Lawrence of Arabia was indistinguishable from sand.

Da Vinci’s The Last Supper with Christ flanked by six disciples. Or so the late Curtis Hanson proposed in a 2009 Turner Classic Movies special, where he, Mr. Mann, Mr. Pollack, and Mr. Scorsese championed letterboxing and condemned pan and scan. Vandalism disguised as convenience! One might roll their eyes at the one percent’s grandstanding, but they were not wrong. Rewatch Disney’s Sleeping Beauty (1959), for example, and you’ll gape at the medieval backdrops cannibalised on your childhood VHS.

Speaking of elite chastisements, another director’s impractical advice graced my Vichy Twitter feed. Paul Thomas Anderson, Mr. Maya Rudolph, wants film bros to see his upcoming One Battle After Another: The Sydney Sweeney Story “the way Nature intended”. Predictably, the response was defensive bravado. “Who cares? I’ll watch it on my phone, eating Doritos and masturbating.”

Can’t you smell the resignation to a world of diminished expectations? Settling for less and paying more for it. Not long ago, ordinary folk insisted on decent speakers for music or “the wireless”. Now, a tinny phone suffices. Podcasts substitute for reading. It isn’t dumbing down, not when you’re priced out of better options. My Instagram AlGore-ithm doesn’t help. Polemics on the “friendship recession” and the decline of “third spaces” abound. Social media, our last public sphere, has curdled into a toxic echo chamber. Outwardly, it’s mocking indifference – “VistaVision? LOL, I’ll stream it on some illegal Russian site”. Underneath, it’s structural exclusion. Most people simply don’t have the choice.

Much as unease around letterboxing once shaped how films were viewed, Anderson’s plea to “see it properly” exposes the tension between aspiration and access.

With pan and scan, cinematographers forfeited their compositions, actors lost their heads, and dialogue drifted offscreen from characters visible in the theatrical cut. It wasn’t ideal, but neither were those black bars that contracted the image to nothing. Are you a well-anndowd boy? If not, consider your own shortcomings. And you’ll know how small I mean.

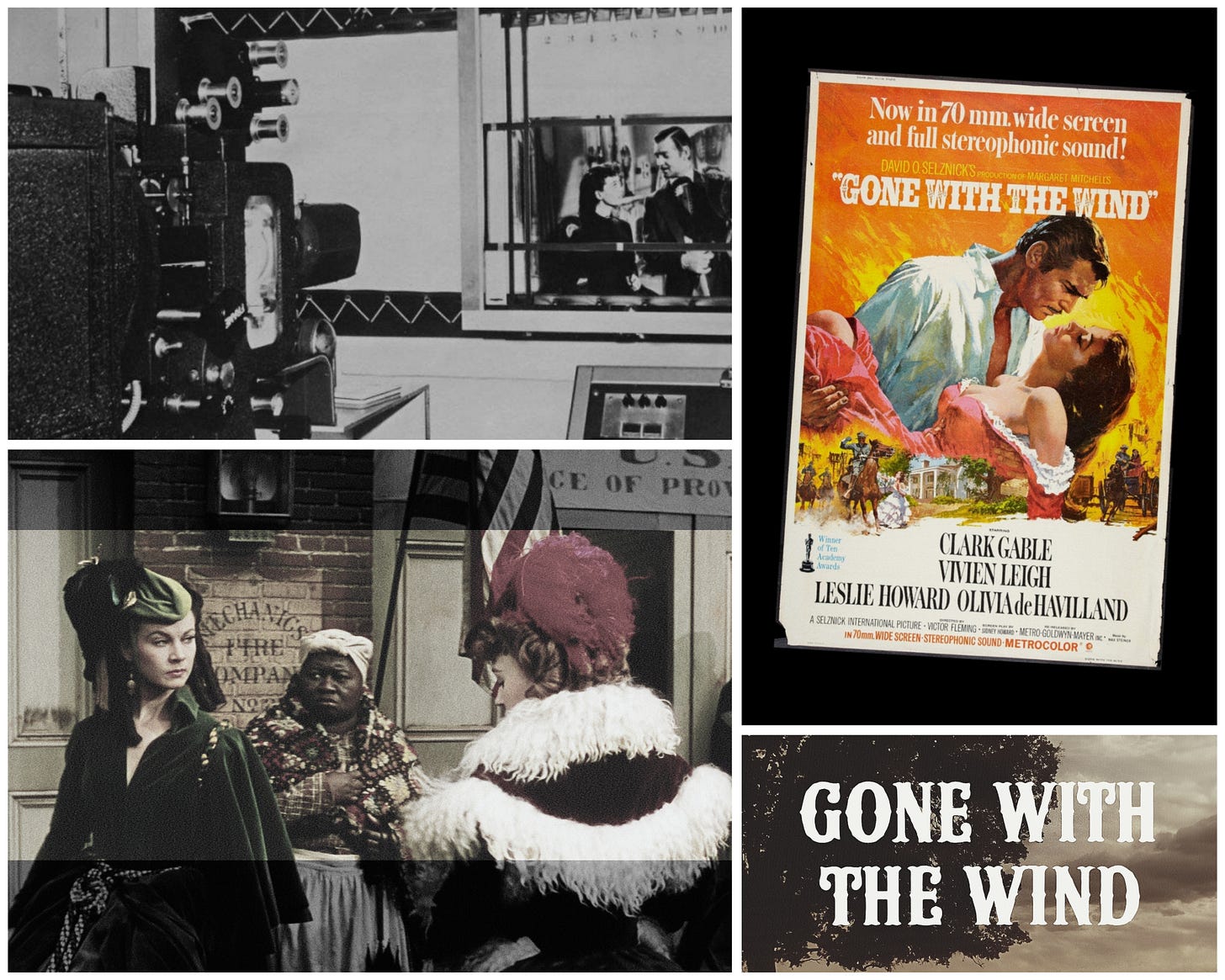

Curiously, this carnage worked in reverse. In 1967, still reluctant to sell TV rights and clinging to the event of revival screenings, MGM’s re-release of Gone With the Wind was, in polite parlance, an abortion. Like Star Wars decades later, “Selznick’s Folly” returned in a series of special engagements that piled damage upon damage. Hollywood never learns: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Each “improvement” eroded the film’s integrity, leaving less for future audiences to cherish.

By 1967, MGM was pawning the commissary silver to stay afloat, yet still chased novelties. Metrocolor that looked muddy. Stereophonic sound that rendered dialogue unintelligible. And “70mm”.

70mm film weds a 65-millimetre image with 5 millimetres of magnetic tape holding up to six audio channels. Overwhelming visuals and a deafening din on supersized screens. Hoping to replicate the success of Ben-Hur, the studio bankrolled a string of ruinous 70mm flops. But blowing up existing films like Doctor Zhivago showed promise. Buoyed, MGM turned to Gone With the Wind, the jewel in their crown. (Metro, who’d distributed the film upon its initial release, inherited it outright after the liquidation of David O. Selznick’s company in the 1940s.) One historian sighed: “Every composition of every scene as visualized by David Selznick, as illustrated by William Cameron Menzies, as directed by Cukor, Fleming, and Wood, as captured by cinematographers Garmes and Haller would be sacrificed on the altar of size”.

The ambition – to “convert” the picture to 70mm – suggested scientific precision. The reality was crude. In layman’s terms, the image was panned and scanned to mimic widescreen, then promoted as if photographed in “new screen splendor”. A contraption called “the Metro Movement” literally re-shot the entire film across nine positions. An ill-advised sound mix added hoofbeats and swishing skirts while burying key exposition. Vivien Leigh was decapitated in several shots. Close-ups cropped Clark Gable at his eyebrows – the oldest trick in every balding man’s selfie playbook. The sweeping opening was replaced with a stationary title card. Roger Ebert noted that the one-strip transfer drained the Technicolor to the level of sepia, forcing later restorers to hunt for alternative three-strip masters. Luckily, they succeeded, though some shots remain forever lost.

Only Helen Keller would’ve called 1967’s Gone With the Wind “a thrill to look at and listen to”. It was ghastly. And those compromised prints circulated for decades. Yet the public came. One legacy endured: Howard Terpning’s iconic poster of Rhett Butler cradling Scarlett O’Hara through the flames.

And I suppose it beats black bars.

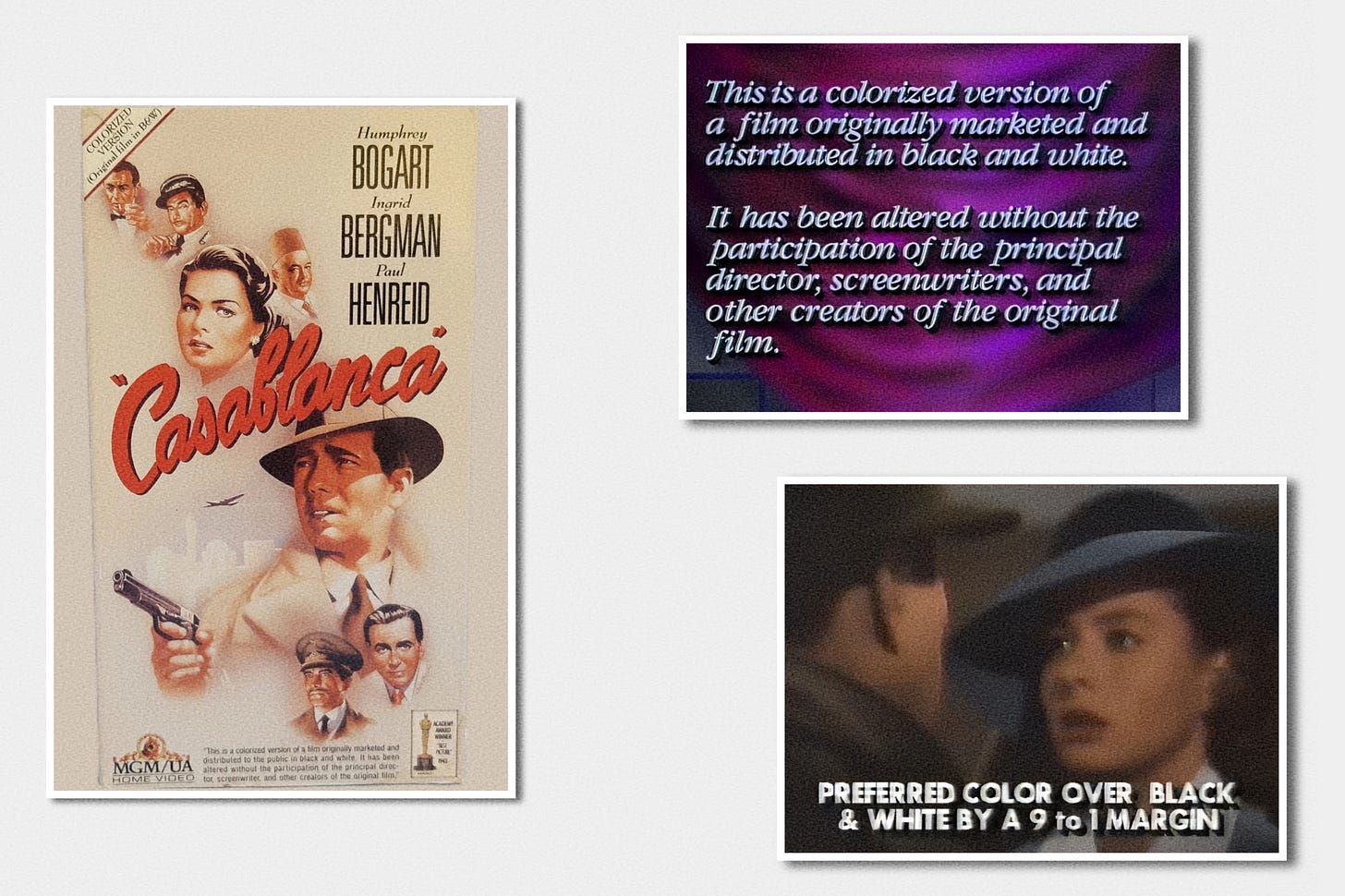

Then came colorization. (I’ll hereby spell it with a “z”, à l’américaine, for consistency.) Ironically, George Lucas opposed it. But in the 1980s, broadcasters claimed boomers preferred a colorized Casablanca nine to one. The then-tenants of the White House signed on – despite Ronald Reagan’s halcyon days as the “Errol Flynn of the B’s” at Warners.

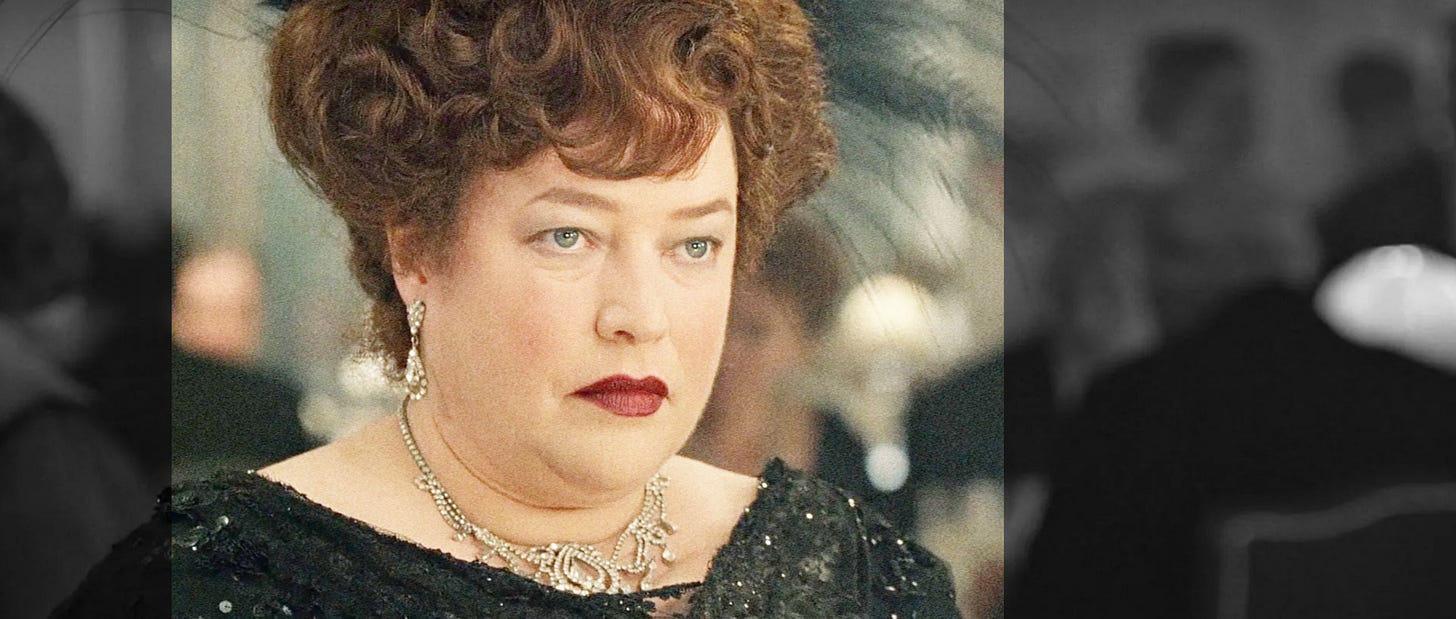

“I can understand the business problems of those who invested the money and know now there isn’t a market for black and white,” the President grumbled. Mrs. Reagan, whose greatest inspiration as an “actress” was the vacuum Kathy Najimy mounts in Hocus Pocus, was more enthusiastic. Shown a pastel print of a Cary Grant film, Nancy gushed, “I didn’t think Topper could ever be improved, but we were most impressed with the colorization of that fun movie. The soft colors were not intrusive but added just the right touch. A clever idea”.

The Reagans’ views aligned more with Ted Turner’s than with their confrères Ginger Rogers or Jimmy Stewart, who fumed at anyone painting their faces like Easter eggs. (Turner, the Atlanta magnate famous for splashing colour onto black-and-white relics, was at one point married to Jane Fonda.) “The last time I checked, I owned the films,” he harrumphed like Ronnie’s proverbial microphone, “I can do whatever I want with them.” (Incidentally, Turner’s acquisition of the MGM back catalogue in 1986 gave him stewardship of Gone With the Wind for a decade, before the rights changed hands. Even Roger Ebert, while otherwise decrying colorization as “Hollywood’s New Vandalism”, praised Turner’s company for reinstating Gone With the Wind’s original ratio for its fiftieth anniversary. A workmanlike blueprint for superior restorations that followed.)

Casablanca, Turner boasted, had received “the best colorization we’ve ever done”. He dismissed dissenters with predictable whataboutism. If black-and-white films were so wonderful, how many had been made last year? Lew Wasserman, the mastermind behind Reagan’s political career and Universal’s pooh-bah, was equally snide. When Missouri Democrat Dick Gephardt objected, Wasserman huffed, “Why is the smartest young man in Congress worrying about who’s colorizing films? Tell him if he doesn’t like them to go to every television in America and take the color knob off”. Like Turner, he shifted blame from tampering studios to complaining spectators.

Given Universal Pictures’ own history of destruction, the deflection was hardly surprising. As historian Kevin Brownlow relates: in 1929, Carl Laemmle Jr., convinced silent prints were worthless in the talkie era, piled them high and set them alight.

Turner insisted colorization wasn’t desecration, but what Old Hollywood producers would have done if they’d had the technology. A convenient claim, since few were alive to argue. He promised experts would consult production notes, storyboards, and archival materials to ensure accuracy before delegating the task to computers. As with MGM’s tinkering on Gone With the Wind, the results were ramshackle. Two weeks before his death in 1985, Orson Welles, outraged at the thought of his masterpiece being altered, thundered: “Keep Ted Turner and his goddamned Crayolas away from my movie!” – referring, of course, to Citizen Kane.

John Huston, who died two years later, was equally outspoken. His daughter Allegra recalls in Love Child: A Memoir of Family Lost and Found (2009) that his films were his “babies”. “People had cut them and mangled them, and now Ted Turner wanted to dye their hair.” Half-sister Anjelica added in Watch Me (2014) that Turner’s efforts sparked an international backlash. After a French network aired a tinted The Asphalt Jungle (1950), a three-year court battle produced a landmark ruling. No colorized film could be shown without the creator’s consent. In the United States, the 1988 National Film Preservation Act went further, establishing the National Film Registry and requiring clear labelling of any alterations, including colorization.

This legal momentum collided with Turner’s most audacious plan: colorizing Citizen Kane. Between summer 1988 and spring 1989, public outcry, courtroom battles, and moral debates crescendoed – until litigators unearthed Orson Welles’s 1939 RKO contract. It gave him unprecedented control over his work. This sweetheart deal made the edits legally impossible. A fifty-year-old document became the death knell of the colorization craze.

And now, after a century of cuts, crops, and colorization, we come to the current calamity. The Wizard of Oz at Sphere.

I’m sure you’ve seen the footage.

Either the bootleg clips from the monstrous Las Vegas premiere a fortnight ago, or the CBS Sunday Morning segment in July that begot the controversy. In which Ben Mankiewicz, Turner Classic Movies host and grandson of Citizen Kane’s co-writer, outed himself as an AI apologist. (That’s artificial intelligence, not “Amy Irving”.) Lorna Luft, the Other Garland Girl, also gave her family’s blessing.

Mankiewicz doubled down on Vichy Twitter, insisting: “All they’re doing is extending performances to fit a large screen – completing work [director Victor] Fleming and [producer Mervyn] LeRoy would’ve if it had been possible”. He added, “It is not the death of cinema. It is literally bringing The Wizard of Oz to a new audience in a cool new way IN A THEATER!”.

With all due respect, at over $130 a ticket, no one is discovering an 86-year-old film this way.

The Wizard of Oz at Sphere is the brainchild of James L. Dolan, Croesus of Madison Square Garden and major donor to Mr. Trump. Dolan’s contempt for his audiences is notorious: his company has used AI and facial recognition to bar detractors from his venues. When Dolan and his fellow producers showed up in full costume to the “grand unveiling” on Thursday 28 August, I thought them losers of the highest order. Extremely wealthy losers, but losers nonetheless. It was painful to watch one, dressed as the Scarecrow, stumble through vacant rows in an arena that’s never fully darkened. As Alissa Wilkinson observed in The New York Times, the giant screen lights the room throughout, killing the illusion of immersion. With most of the crowd glued to their phones under the blinding glare, I couldn’t imagine a less pleasant way to endure “The Wizard of Oz as you’ve never seen it before!”.

Critics describe an unsettling “uncanny valley” effect. Munchkins and Emerald City denizens glitch like corrupted Sims, while an AI-generated Kansas cottage bashes about the 160,000-square-foot screen like a garish screensaver. The “practical” effects fare no better. Foam apples fall during the talking trees vignette, while wind machines and paper scraps approximate the tornado. It’s a far cry from 1939, when MGM’s special effects maestro Buddy Gillespie created the twister with nothing more than a nylon stocking and a Monopoly house.

Worse, the film’s airtight runtime is relieved of over twenty-five percent to accommodate more showings. Ms. Wilkinson was informed this 75-minute cut suits contemporary tastes, a claim she finds “depressing and dubious”. And no, you don’t get to keep the foam apples. The obscene pricing fosters a culture of forced praise, much like Broadway’s mandatory standing ovations. Playgoers cheer like trained seals to justify their expenditure. Gouging disguised as an “experience”.

And, of course, no one can put their bloody phones down.

It’s easy for me, a keyboard warrior, to mock what others enjoy. I don’t wish to be a curmudgeon, but the justifications for The Wizard of Oz at Sphere are as old as time immemorial. We heard them during colorization: that reverent research and technology “honours” the original. Isn’t Jim Dolan’s bluster about “ethical AI” just the same old strawman? Then there’s the lure of exclusivity, à la London’s ABBA Voyage. You’ll only see it here. This site-specific effort inflicts as much harm on the prototype as, say, Disneyland’s Star Wars attractions do to those films. (Naturally, the Star Wars in the National Film Registry isn’t the real one, just as it’s misleading to call Episode IV: A New Hope an Academy Award-winner when the elements that earned those Oscars have been erased in every available version.)

No one is damaging the original. In any event, The Wizard of Oz has been meticulously restored over the years. (It was Ted Turner who reinstated the Kansas scenes to their correct sepia for the film’s semicentennial, replacing the cheaper black-and-white used in re-release prints.) Moreover, it still resembles a 1939 production – gloriously so! – unlike the increasingly dated Star Wars. Even the fan-made “despecialised” versions are stymied by their illusion-shattering 1977 look. By contrast, Oz remains timeless. I first wore it out on VHS as a child, watched it endlessly on DVD as a teenager, and recently – aged [redacted] – revisited it on streaming. Another memorable viewing occurred on a transatlantic flight. At every stage, in every vulnerable moment of my life, it lands with the same emotional heft. It doesn’t just take you to Oz; it transports you to Glorious ’39. The peak of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer dream factory, its master craftspeople, and their boast of “more stars than there are in Heaven”.

That’s what makes the Sphere so offensive. It strips away the magic, swapping painted sets and pantyhose for literal, photorealistic clouds and mountains. Judy Garland and her three vaudeville hams are flattened into cartoon cutouts. Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch – ranked the fourth greatest villain and the greatest villainess by the American Film Institute in 2003 – is a shrew in prosthetics, absurdly magnified across a screen three football fields wide. What was once flesh and blood is now a gimmick.

As Alissa Wilkinson asserts, it’s not unlike those “Van Gogh Experiences”. But visitors to those (often fraudulent) VR exhibits – virtual reality, not Vanessa Redgrave – would never mistake the simulation for seeing Vincent van Gogh’s actual paintings. Moral concerns aside, those shows make no bones about being ersatz. The Sphere, however, blurs that line. Its patrons are even less discerning. Wilkinson fears they might not realise how profoundly the film has been altered, despite the 1939 credits bracketing it.

And that, to me, is troubling.

I haven’t been to a cinema in three years.

That’s due to a strong dislike of them as much as my “would-peel-an-orange-in-his-pocket” tightness. Last week, someone suggested Downton: Soulless Cashgrab. (Let’s face it, only marginally worse than the actual title, Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale.) I proffered vague excuses. I always find such excursions deeply unenjoyable.

I can’t bear not paying in cash. And I loathe the umpteen ticket tiers (even for a 9 a.m. Saturday showing, my old trick to avoid seeing gay people). There was a time one could just steer clear of the city centre to avoid “luxury” cinemas and the trust fund transplants that haunt them. Now, there’s no escape. Any suspension of disbelief is shattered by the pong of fresh paint or ancient popcorn crusted into the “settee” seating, and the inevitable glow of phones at crucial moments.

Perhaps, “boutique cinemas” are another component of the calamities we’ve spoken about today. Hollow spectacles all!

Each promised innovation or accessibility, yet turned what should’ve been pleasurable into rackets. A capitalist farce sold as democratising improvement. Some of these ambitions were well-intentioned, but all were disasters. The common thread, to my mind, is the immolation of human artistry. Craft and composition traded for novelty, convenience, and profit.

It leaves us, like Little Mark rewinding his Star Wars trailer, grasping for the wonder that once made movies Our Own Private Oz. In the words of Blanche DuBois, “I don’t want realism. I want magic!”.

Glued to our screens, we watch more, but see less. We’re incapable of allowing our imaginations to breathe.

Read Next:

Little Miss Sunset & The Trials of Norma Desmond

“I remember the first Met Gala… The theme was ‘The Wheel’.”

Viv, Larry, and the Great Anglo-American Film War

Love your commentary and your (our) love of classic cinema. Thank you for describing the craven soulless money grabbing going on in Vegas by major MAGA asshats. I stopped going to the theater and the cinema due to reasons you describe, and would prefer to watch a film on my old tube TV, which I keep so I can watch all my VCR tapes. It is hooked up to a very good sound system and I can pop my own corn. Of course, I also invested in DVDs so I have that option as well. There's no place like home. Cheers~