Elevating Rita

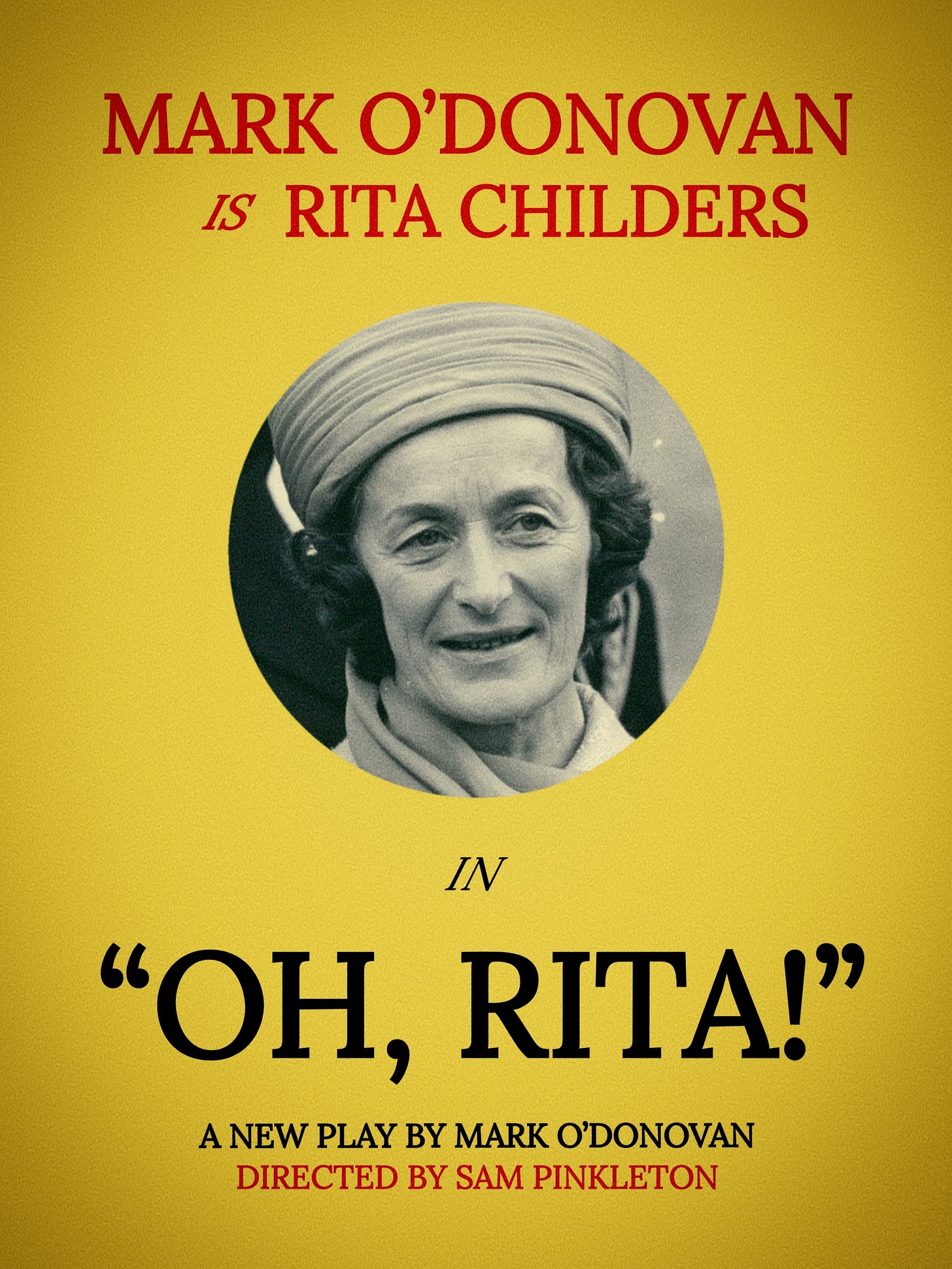

Now! A warning! This week’s Substack leans domestic – which here means: Dirty Dublin, not cooking and cleaning – though non-nationals should still find it diverting. It concerns a wonderfully odd chapter of Irish politics, largely unknown to me: in which Mrs. Erskine Hamilton Childers, widow of our only president to die in office, very nearly became First Citizen herself.

I. Denial

“England’s difficulty is Ireland’s gain.”

Never was this maxim truer than Christmas 1936. In the Year of the Three Kings, the Free State stood at a crossroads. Éamon de Valera, President of the Executive Council, had spent four winters chipping away at British control. The monarch lingered as head of state, but his presence had shrunk to a single figure: the Governor-General. Installed in a Dublin council flat rather than the Viceregal Lodge, the sovereign’s representative shirked his duties on Dev’s command. In the south, royal influence was a formality.

Meanwhile, in London, His Majesty’s infatuation with Mrs. Ernest Simpson – a socialite with two living husbands and, worse, an American – dealt the Irish a firm hand. The Dominions Office warned that without prompt action under the Statute of Westminster, Edward VIII, even after renouncing the throne, would remain King of Ireland, with Wallis as his queen. (I’ve always thought that a splendid arrangement!) Dev seized the chance. He pushed through legislation stripping the Crown of its remaining powers and laid the foundation for an Irish republic.

A year later, Bunreacht na hÉireann, the 1937 Constitution, dissolved the Free State apparatus. It introduced a bicameral parliament, the Oireachtas, at Leinster House. Comprising a lower chamber, the Dáil, and an upper chamber, the Seanad. Executive authority rested with the Taoiseach or Prime Minister. And the Governor-General? Gone. Replaced by a ceremonial but directly elected President of Ireland. This was no accident. In an age of dictatorships, even a ribbon-cutter required the legitimacy of the ballot box. The Viceregal Lodge was repurposed as “Áras an Uachtaráin”, his official residence.

Enter Douglas Hyde. At 78, he was the revered founder of the Gaelic League and Protestant in a Roman Catholic country. As Ireland’s inaugural “First Citizen”, Dr. Hyde shaped the presidency as an emblem of national unity – above party politics. This was no hidden lever of power, merely Éamon de Valera’s retirement. In 1959, Dev stepped down as Taoiseach, but remained figurehead of the state he’d forged until 1973.

Alas, “Queen Wally” hadn’t finished with Irish constitutional affairs.

II. Anger

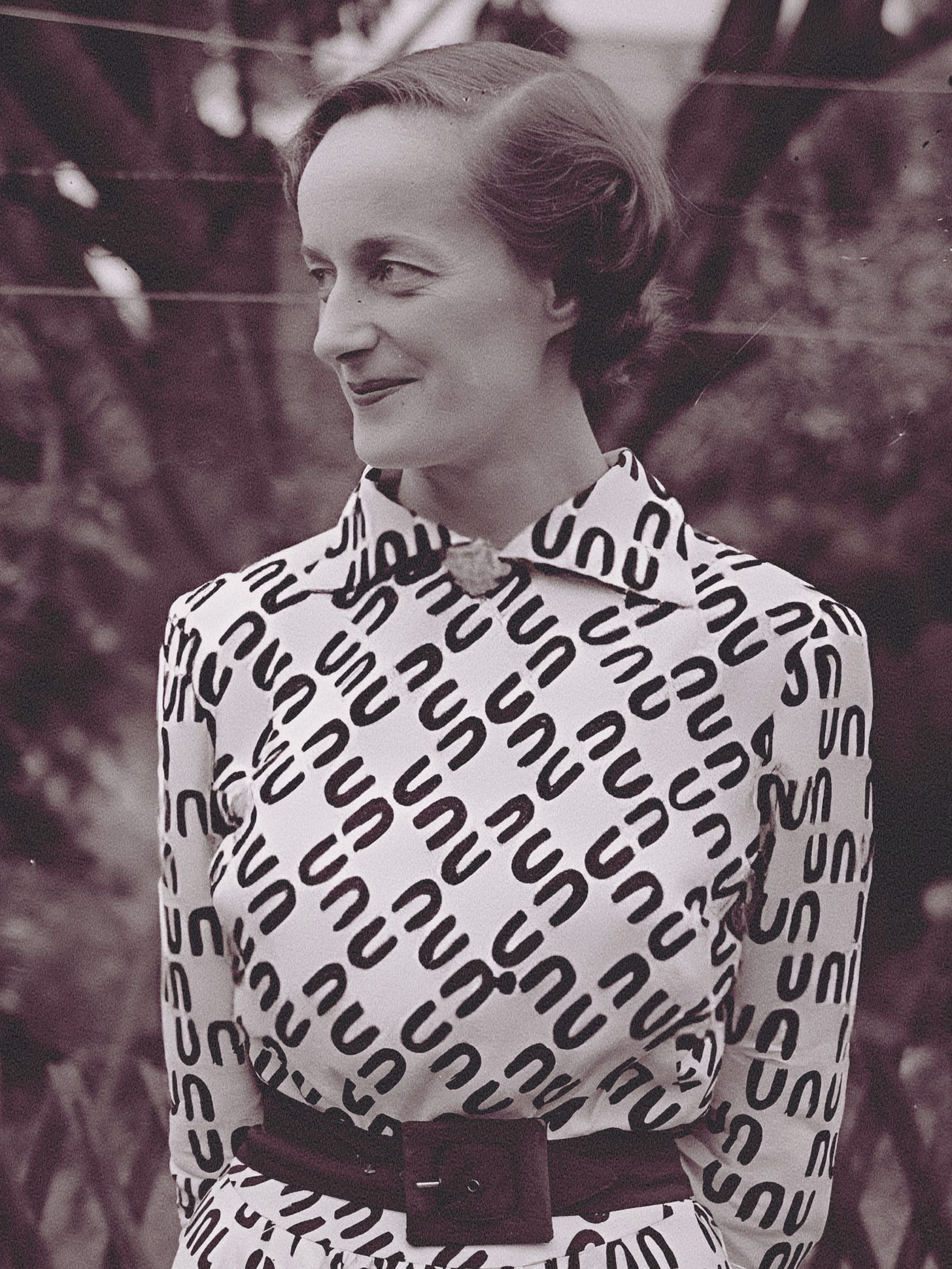

Margaret Mary “Rita” Dudley (19 July 1915 – 9 May 2010) so closely resembled the Duchess of Windsor that wags christened her “Wallis”. Born into a Catholic family in Ballsbridge, she was thrust into early adulthood. Her father, a Dublin lawyer, died before her fourteenth birthday, dashing any chance of the university education she prized.

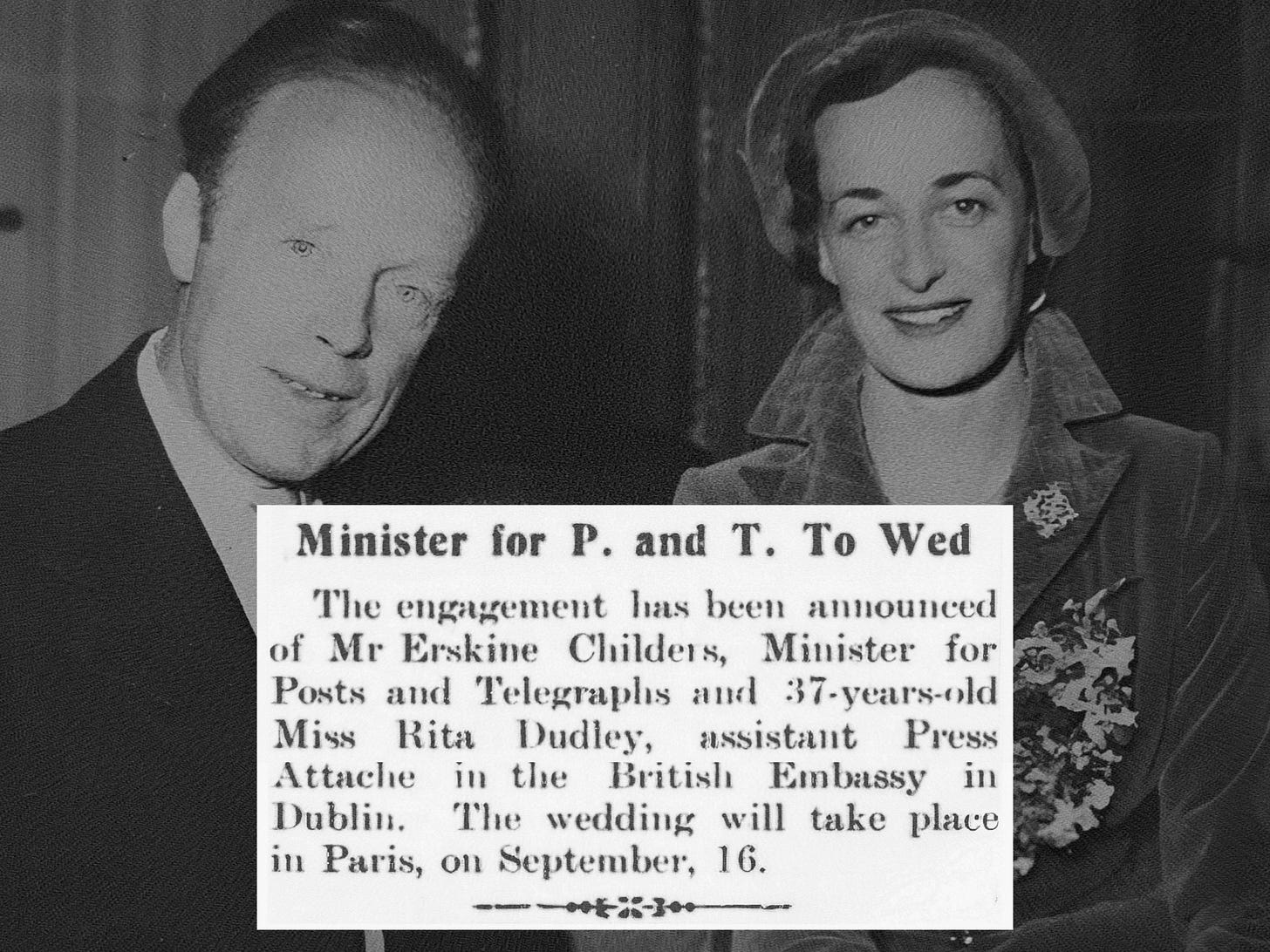

Initial work in the inner city honed Miss Dudley’s empathy, managing soup kitchens for malnourished mothers. Rita parlayed her intellect, charm, and poise into a diplomatic career. She served as Assistant Press Attaché at the British embassy and later the British Ministry of Information in London. This heady mix of grit and grace caught the eye of Erskine Hamilton Childers, a widower with five children, in 1952. A government minister ten years her senior, Childers was the “odd man out” of public life. An Anglo-Irish Protestant, a liberal voice in Fianna Fáil (the Republican Party), and son of Robert Erskine Childers, author of The Riddle of the Sands, executed in 1922.

The Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, opposed their engagement. He took umbrage at Miss Dudley’s circumstances: a career girl of thirty-seven with no dowry. He refused to sanction the nuptial Mass that Rita, a daily communicant, craved. She bartered with His Grace. She’d forgo a wedding dress and bridal entourage. All she sought was a church. McQuaid was unmoved. With no other choice, they wed in Paris on 16 September 1952. Rita, clutching an exemption from her parish priest, got her altar. “To think, even at thirty-seven, I could feel so happy and pleased with the world!”

The Childerses were quintessential Irish eccentrics. Weekends meant walking the Wicklow hills, putting the world to rights. Their voices captured genteel pasts. Rita’s, a “relic of auld decency”; her husband’s, clipped Cambridge. They were expert cooks, skilled gardeners, and discerning sartorialists. (Erskine, it’s said, occasionally chose the fabric for Rita’s frocks, like Oscar Wilde dressing Constance to match the soft furnishings.) Acquaintances weren’t drawn from the back-slapping world of Leinster House, but from artists and intellectuals. In McQuaid’s theocracy – clerical control shaping Irish policy from 1940 to 1972 – they advocated for contraception and public health reform. It was Erskine who appointed the first woman, Dr. Thekla Beere, to head a civil service department. And Rita was more than a political spouse, she was his closest adviser. The effect was Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter without peanuts. To Irishwomen, she was impossibly glam. Thin, stylish, their own Diana Vreeland. And that mattered.

Rita was an outlier, too. Her wartime service proved controversial, though she never saw it as a betrayal of neutral Éire. While Hyde and de Valera sent condolences to Hitler’s envoys, Rita absorbed uncensored reports of Nazi atrocities. Encounters with sex workers during the Blitz furthered her lifelong commitment to the disenfranchised. When the Troubles erupted in Northern Ireland, Rita was indispensable: Erskine’s insider on British government strategy. Those were dark days. Kidnapping became a genuine fear – for her and their daughter Nessa (born 1956). “If it happened to you,” Erskine quipped, “we couldn’t give in. I could never agree to a ransom demand.”

“My mother, Rita Childers, was ahead of her time,” Nessa Childers recalled, “a highly intelligent, remarkably resilient woman. She was never afraid to speak up and to speak out.” In a country where over half the population lived under rigid legal and social strictures, that took gumption. Chief among these was the Marriage Bar, a law forcing most women to resign upon their weddings. Ireland did not repeal this stark symbol of gender inequality until July 1973.

Two months earlier, Rita waded into uncharted waters.

III. Bargaining

Erskine H. Childers was elected Ireland’s fourth president in May 1973. His opponent, Fine Gael’s Tom O’Higgins – who’d come within a hair of unseating Dev in 1966 – was expected to win.

“Being president of Ireland,” wrote Anthony Bailey in The New Yorker, “is like being both Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip.” The role mixes the constitutional duties of a monarch with the cause-promoting, but apolitical, work of her consort. Childers envisaged an activist First Citizen, outside parish-pump pursuits.

Fianna Fáil was doubtful. Voters were not. He won by four points.

Childers ran Ireland’s first modern campaign. A “Childers for President” bus crisscrossed the provinces, lending him energy and accessibility. His regal manner and accent reached far beyond his party’s traditional base. (Never underestimate the Irish people’s love for “a character” – especially among society’s richest or poorest. Those in the middle, like me, are just “autistic”.) Erskine, a former ad man, combined simple but striking messaging with Rita’s public relations flair. An approach so timeless, it would resonate today.

Rita set the tone. “She was in many ways more savvy than my father,” Nessa Childers enthused, “and a good speechwriter! Always handy.” Her sangfroid made the difference. She connected with common folk, telling a ladies’ magazine it was women, the majority minority, who’d get him across the line. She sidestepped pitfalls, principally her husband’s ineptitude in the Irish tongue. A quick-thinking Rita insisted Erskine daren’t insult native speakers by feigning fluency. (Erskine having once derided traditional music as “squealing pipes and women wailing by the fireside when it’s an image of a modern Ireland we wish to present to the world”.) And yet, even in the Gaeltacht, those fiercely proud regions where English is taboo, locals warmed to the colourful couple. The Irish didn’t just like Erskine Childers. They saw him as their own.

On 1 June 1973, Rita’s acumen was put to the test. She arranged her husband’s victory conference, an impromptu celebration few believed possible.

Unlike his three predecessors, with “nothing to do and all day to do it”, President Childers significantly raised the role’s civic profile. He desired a think tank to plan Ireland’s future; public access to Áras an Uachtaráin and its grounds in the Phoenix Park; and a more engaged office. It wasn’t to be. A hostile government stymied his efforts at every turn. No one knew, either, that the president was on borrowed time. Sixteen months later, while addressing a conference of Dublin medics, the First Citizen was felled by congestive heart failure.

On 16 November 1974, Erskine Hamilton Childers collapsed, turned blue, and died within moments. His passing plunged Ireland into a political crisis, with Rita at its centre.

IV. Depression

Article 12.3.3° of the Constitution stipulates that, in the event of the president’s death, resignation, removal, or incapacitation, an election must be held within sixty days. Outwardly, Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave’s Fine Gael-Labour government and Jack Lynch’s Fianna Fáil opposition presented a united front, maintaining decorum as they organised the state funeral. Inside, it was chaos.

Ireland has no vice president, nor parliamentary mechanism to appoint its head of state. The framers of Bunreacht na hÉireann hadn’t foreseen postwar ceremonial presidencies, like those of Germany or Israel, where an electoral college decides. In the week beginning 18 November 1974, politicos floated such innovations, knowing they’d require a referendum. But as the country mourned, Cosgrave and Lynch were in agreement. With the cost and awkward timing before Christmas, an election was out. Regardless, the law was clear. A new president had to be in office by 16 January 1975.

While Rita Childers grieved in widow’s weeds at the Áras, Leinster House focused on another presidency. That of the Council of Ministers, the six-month rotating stewardship of European policy coordination. Ireland’s first term was set for January-June 1975. (Incidentally, earmarked by the United Nations as “International Women’s Year”.) It was unthinkable to begin the E.E.C.’s mandate on New Year’s Day without a head of state. Therefore, the Friday before the winter recess was earmarked as the last viable date for an inauguration.

Even with a consensus candidate, protocol required nominations to close on 3 December, with an election, if required, on the 18th. A runner needed support from 20 Oireachtas members or four city or county councils. It sounds simple, but the parties, having long dominated these channels, make it nearly impossible for outsiders to gain traction. If Cosgrave and Lynch’s nominee secured these signatures and no challenger emerged by the deadline, the presidency would be filled without a popular vote. As happened with Douglas Hyde in 1938 or Seán T. O’Kelly’s unopposed second term in 1952.

Rumours swirled about Cosgrave and Lynch’s dream man. A celebrated ambassador or jurist, for preference. Someone like Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh (anglicised as “Carroll O’Daly”), the brilliant but bonkers former Attorney General and Chief Justice, then serving in Luxembourg. A figure with public credibility, international stature, and “youth” on his side. “Youth” was relative. Aspirants were in their sixties and seventies – hardly at death’s door, but expected to last a full term.

On 21 November, the night of Erskine Childers’s burial, Fianna Fáil rank-and-file pushed a different tack. Their leader, Jack Lynch, should be “moved upstairs”. For Lynch, it was a grim prospect. Seven years in exile, abandoning any hope of returning as Taoiseach and exorcising the humiliation of opposition. In the 1973 general election, Fianna Fáil had won the most seats (“Tell me about this chap, “Jack Leads”!” Rita jibed, eyeing poorly designed campaign badges), but failed to retain power. After sixteen years, Ireland’s dominant force was ousted when Fine Gael and Labour brought political realignment amid a sour economic mood.

The next day, Chris Glennon of the Irish Independent analysed contenders to become the fifth president. Column inches were devoted to Lynch, Judge Ó Dálaigh, Seán MacBride, Freddie Boland, T.K. Whitaker, and other heavy-hitters. But Glennon offered a tantalising twist. “It is believed the Government has another name in mind, but so far, the identity of their main candidate has been kept secret.”

In Dublin, thirteen housewives pitched a solution. Unfazed by protocol or party politics, the ladies of Rochestown Avenue wrote to The Irish Times. They proposed a president who combined diplomatic experience with erudition. An internationally renowned figure, trusted by the public. In fact, their candidate met every criterion of the parliament. Their nominee? Mrs. Erskine H. Childers.

It wasn’t so far-fetched. Rita Childers was no ordinary Irish political widow-woman. Not that Irish political widow-women (or Irish political orphans, for that matter) ever shied from contesting Dáil seats vacated by their husbands and fathers. Unbeknownst to these doughty campaigners, the idea that Rita might take up her husband’s mantle was already under serious, if reluctant, consideration. Cosgrave’s coalition saw the potential. The opposition was less keen, but Lynch, eager to silence rumours he wanted the job himself, recognised its appeal. Was this the compromise? Mrs. Childers, after all, was tied to an extremely popular president’s legacy. To mute the sceptics, it could simply be presented as finishing her husband’s term. Cometh the hour, cometh the (wo)man.

Now, Rita’s family – the Dudleys – were dyed-in-the-wool Fine Gael. This was a stumbling block. Lynch had to prove that Erskine’s win for Fianna Fáil was no fluke. The government denied a protest vote, crediting Childers’s batty charm. But Lynch wasn’t buying it. Partisanship prevails. Tribal politics don’t disappear overnight – especially in Ireland, where such loyalties run deep, even if they’re rarely spoken aloud. (Tellingly, the press largely ignored how Erskine’s father had been executed by the Free State under orders signed by Kevin O’Higgins, his opponent’s uncle.)

Still, fifty years after the Civil War, Fianna Fáil seized the presidency in May 1973. It was theirs. To hand it over to a Fine Gaeler in December ‘74 – even if she was his widow! – was risky. It smacked of surrender. But Rita had the public’s sympathy and media on her side. She would be unbeatable. Cosgrave and Lynch tossed around other names, Judge Ó Dálaigh among them, but no one came close. Jack Lynch agreed. On one condition: it would remain secret until he’d secured his party’s consensus.

Akin to the Protestant wind that foiled the Armada, the Titanic’s missing binoculars, or the Archduke taking the scenic route through Sarajevo, happenstance scuppered the plan. The fiasco began in Skibbereen, County Cork. A well-meaning urban councillor, fond of florid oratory, endorsed Mrs. Childers. He called her “a woman of humble origin who’d advanced herself by her scholarship” and “the power behind the President”. As the local authority route for presidential nominations wasn’t successfully exploited until 1997, it was a fool’s errand – but Grub Street lapped it up.

The press, like this alderman, was oblivious to clandestine negotiations above in Dublin. A journalist collared a Fine Gael minister for comment. Partially deaf, Minister Tom O’Donnell assumed the story had broken and confirmed the coalition’s intentions. By 24 November, variations on “Mrs. Childers for President!” blared from every Sunday paper. Lynch was livid. He accused Cosgrave of a set-up. His party’s delicate support for Rita collapsed. And just like that, Ireland lost its chance for a “Lady President” – sixteen years before it had one.

That’s where most versions of the story end. But Rita wasn’t going down easily.

V. Acceptance

On 26 November, the same day Rita and Nessa were given two weeks to vacate the Áras, Jack Lynch dispatched two Fianna Fáil deputies to the Park.

Historian Bernadette Whelan, in the compendious Irish First Ladies and Gentlemen, 1919-2011, considers this a deliberate move. Intended to wheedle Mrs. Childers into a public rebuke of the coalition. But instead of approaching her directly, their message was relayed through an intermediary, her stepson Erskine Barton Childers. (In a government memo, Cosgrave suggested first consulting her brother, Anthony Dudley – a tone-deaf, paternalistic gesture that reduced the country’s most prominent woman to the status of a ward.) Some accounts say Rita wasn’t home when David Andrews and Michael O’Kennedy arrived. But in his memoir Kingstown Republican, Andrews insists otherwise. “We told her son that Fianna Fáil would not be backing her for the presidency. After Erskine Junior carried this news to her, he returned to tell us that his mother had no wish to see us.”

Did she smell a rat?

There was no love lost between Mrs. Childers and certain factions of her husband’s party. With bald tactlessness, critics branded her a presumptuous widow – clinging to his coattails. Barely a week after burying him, mind. “President Rita Childers”, they mocked, was befitting a banana republic, not a democracy. Misguided and cruel. By all accounts, Rita could have achieved a presidential seal on her own merits. As Nessa Childers put it, “She would’ve been an outstanding president, totally separate from being my father’s wife”.

The Andrews and O’Kennedy episode deepened their sexist bias. The notion that “Reeter” was angling for power, however, is absurd. Just five months earlier, Isabel Perón had taken charge in Argentina, a widow’s succession that made her the world’s first female president. (There’s no musical about that, by the way.) But the historic milestone did little to calm Dublin’s political class – “We would become a laughing stock abroad!”. Sadly, with or without Rita’s Machiavellian manoeuvres or hard-of-hearing ministers, the outcome was inevitable. Ireland would block a second.

On Thursday 28 November, Rita announced her willingness to stand as a non-party nominee. But goodwill vanished. The establishment closed ranks around Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh. Twenty signatories from Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, and Labour furnished his nomination. Seán Dublin Bay Loftus – a maverick, famous for adding causes to his name by deed poll (in this case to highlight coastal erosion) – urged councils to reject the stitch‑up. Let the people decide! Rita had been used, Loftus claimed, and it was high time to get her on the ballot. A lost cause. The deadline passed, and on 3 December, Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh, the uncontroversial and safe choice, was President-elect.

Rita congratulated Ó Dálaigh and his wife, calling them “distinguished, cultured people, each in their own right”. Yet she declined to attend his inauguration, choosing instead a private meeting with the couple. By then, she and Nessa settled into modest, temporary lodgings at the Sandymount Hotel.

Rita felt bruised. Understandably so. But unshackled from the niceties expected of her, she finally had the freedom to set the record straight.

“On the eve of International Women’s Year,” Mrs. Childers implored, “Ireland can no longer afford to have fully half its citizenry treated with condescension.”

Rita, I imagine, would have counted herself a lucky exception. The individuals described in Thekla Beere’s recent Commission on the Status of Women report were the rule. It found that only six percent of married women worked outside the home, while unwed mothers, deserted wives, and widows were left destitute. The government wasn’t wholly heartless. “Good provision for widow!” cheered the Independent, gleefully listing the (income‑tax‑bound) benefits Mrs. Childers would receive, “providing she is not the next President.”

Nonetheless, Mrs. Childers hoped the nation would “put behind us these past wounding, ungracious days”.

Her plea was echoed by Brendan Halligan, a Labour senator, who warned the turbulent fortnight was the tremor revealing a deeper fault line. A popularly elected government and president could clash. A “dangerous contradiction”. Two years later, this fear came true.

In October 1976, Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh resigned after a minister, furious over a constitutional dispute, labelled him a “thundering disgrace” – the most printable version of a much harsher remark. Appalled, Rita again condemned the “corrosive, destructive cynicism” infecting politics. She insisted Ó Dálaigh upheld the presidency’s dignity, as Erskine had, and as she would have, too. Even so, she called for the office to be temporarily suspended.

She delivered a similarly stinging rebuke when Fianna Fáil invited her to a Requiem Mass for deceased party figures:

“The late President would not benefit from the prayers of such a party. Happily for him he is now closer to God and will be able to ask His intercession that his much loved country will never again be governed by these people.”

Life went on. Rita swapped chauffeured cars for public buses, a practical choice given her growing demand on the speaking circuit. At community events, she championed progressive causes, memorably the 1979 sit‑in against the destruction of Viking Dublin at Wood Quay. She soon emerged as a cultural fixture. In the RTÉ Archives footage below, she holds court at a literary gathering. Her patrician bearing unmistakable, she carries herself like royalty. “Queen Wally”, indeed.

I considered closing with a glimpse of the erstwhile Miss Dudley at the inaugurations of Mary Robinson or Mary McAleese – a reminder of the “Lady President” who might have preceded them. But here, Rita’s wisdom rings true. She is speaking about far more than book prizes. Mrs. Erskine H. Childers had integrity in spades.

And her well-earned advice endures. You really cawhn’t please everyone.

Read Next:

Little Miss Sunset & The Trials of Norma Desmond

“I remember the first Met Gala… The theme was ‘The Wheel’.”

Viv, Larry, and the Great Anglo-American Film War

I Know Why the Songbird’s Caged