Clara Blandick, Auntie Em to you and I, isn’t credited in The Wizard of Oz’s opening titles and is penultimately-billed – after a flying monkey, but before Toto – at its close.

She was paid $750 for a week’s work. Not bad going! That’s roughly $16,440 in today’s money. If I had that much, I’d go to the pictures to see The Zone of Interest and maybe buy a multipack of Diet Coke. They’ve just brought in a dreadful levy on single-use plastic in Ireland, you see. Oh, I can’t be doing with this nanny state nonsense! No more than the minimum pricing on alcohol, it’s nowt but penalising the poor sod who enjoys his few cans at the end of a week. We recycle diligently, anyway, and pay for the privilege with that green bin. The aunt in Holland doesn’t even wash her yoghurt pots out before chucking them – and they leagues ahead of us in sustainability…

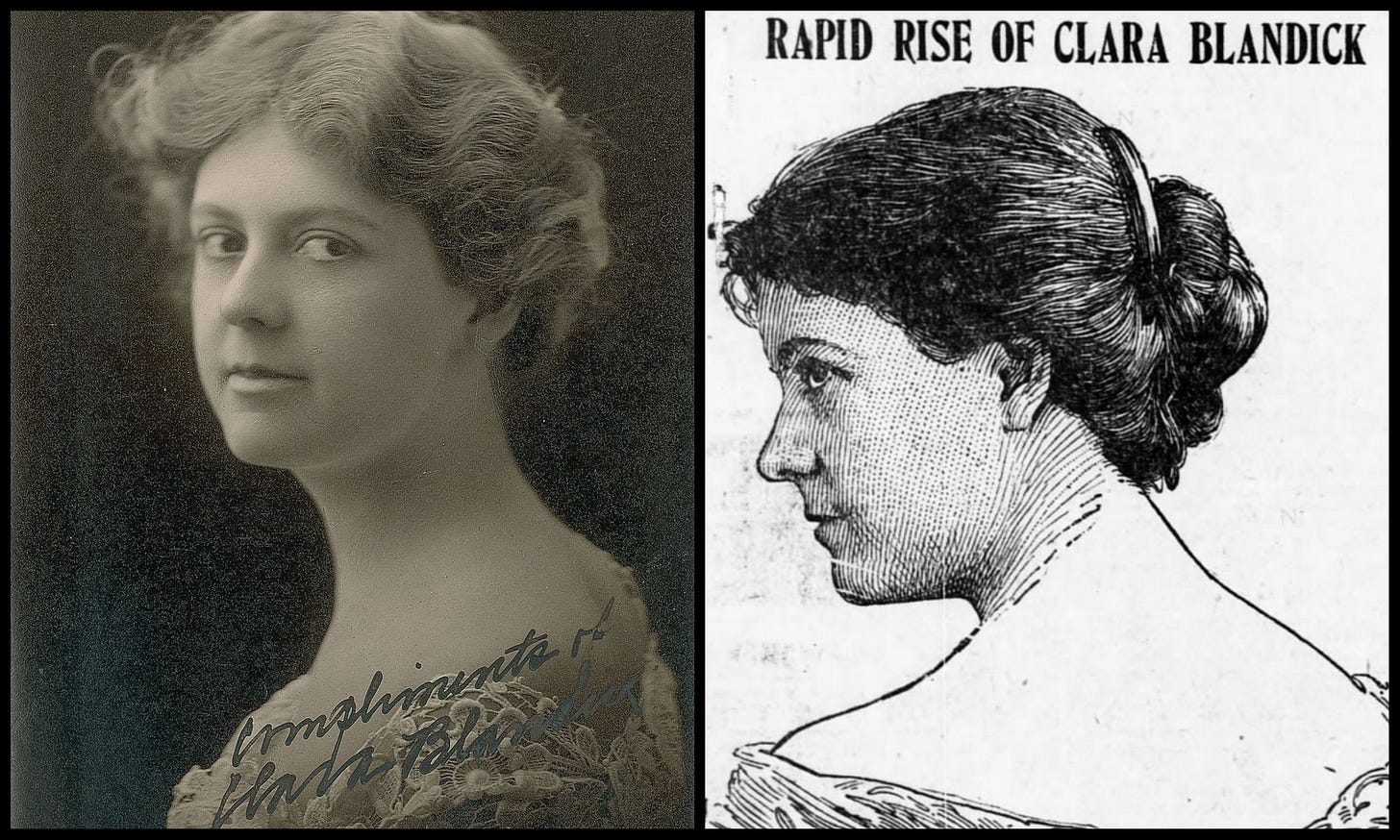

Let’s talk of nice things. Or perhaps not as today’s subject had rather a sad end. I never know who I’m going to write about on Oh, Shut Up! until some fairy or fishwife comes to me like the lightning at Damascus. Roddy McDowall, Laird Cregar, Daphne du Maurier and now Clara Blandick. “Blandick” was a portmanteau of “Blanchard” – after William H. Blanchard, the ship’s captain who delivered her – and “Dickey”, her own patronymic. The Dickeys were a seafaring family; she was born in Hong Kong Harbour in 1876. She claimed it was “1880” – like my pal who puts a number in the high nineties at the end of his email address to throw people off the scent.

“Blandick” inevitably became “blandish” in withering reviews. Ruth Gordon, who toured with her in stock, notes the even less flattering moniker the company gave her: “Constipated Clara”. (As I well know, being a martyr to my bowels and looking like Baby Jane after whatever happened to her happened to her, “pretty privilege” is very real.) Miss Blandick’s métier was spinsters and fretting old ladies. Nobody played thwarted ambition like her – although God knows, Narcississy Spacek here tries! I can’t explain it, but my relationship status is somehow “widowed” despite never having been married; Miss Blandick did walk down the aisle once. Her childless union with miner Harry Stanton Elliott ended in divorce after a seven-year-itch in 1912.

With her ebony eyes, face like the back of a bus, and greying hair swept into a severe bun, Clara looked older than her years. It’s hard to believe she was ever a soubrette, but our “dainty, petite, graceful heroine” entertained American troops in France in 1917. In silent films, her proletarian image served her well. With the advance of talkies, her foghorn voice was a boon! Here’s a clip from 1937’s A Star is Born which lapsed into the public domain when Warners, purveyor of its remakes, forgot to renew the copyright. Blandick spars opposite Janet Gaynor and the venerable May Robson (who later rejected the “lightweight” role of Aunt Em herself). If you’ve ever wondered how the Widow O’Donovan reacts when he encounters a perfectly nice gay guy happily living his life, this is the clip for you.

(Particularly if he’s been privately-educated.)

“When Aunt Em came there to live she was a young, pretty wife. The sun and wind had changed her, too. They had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now.”

— L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900)

Growing up, I knew several Aunt Ems. The hardscrabble world of low-born battleaxes. Women who never questioned anything; who took whatever life threw at them without so much as a by-your-leave. Their ignorance and hearsay was as good as your knowledge and experience. Notions above one’s station were to be clipped early doors. Women who had a comical deference to authority – who bore more resemblance to the Aunt Em of Noel Langley’s 1938 draft than the finished film. The Wizard of Oz being a notorious hodgepodge – with more screenplay contributions than a Beyoncé album. “You have disobeyed your uncle and myself,” Langley’s Aunt Em sermonised “so you have only yourself to blame for your punishment”. (I can almost hear my mother saying “Who are you to know better than the lecturers?” when I dropped out of Trinity for no reason – “oh, you couldn’t-be-told!”.) John Lee Mahin, Victor Fleming’s script fixer, wisely transposed Em’s spite to the figure of Almira Gulch. Moreover, he invented an explanation, other than capricious cruelty, for her disinterest in Judy Garland’s Dorothy. In the opening scene, an incubator has broken down and she’s scrambling to save the baby chicks.

John Waters famously wondered why the foundling wanted to return to “that dreary farm with her grouchy Auntie Em”. “Why go home when you’ve got a gay lion, the best shoes in the world and an elegant castle filled with winged monkeys?” Indeed, Aunt Em (and Uncle Henry) are the only Kansas figures not to be resurrected in the fantasy sequences. Otherwise, there wouldn’t be any impetus to go back! Like Dorothy, I always felt alienated from my family – “They don’t understand you at home, they don’t appreciate you!” – but nonetheless covet their approval. Frankly, at this stage, I think my parents would prefer if I was some camp hairdresser. Who earns enough to barely run a car, and wants only to dance to “Agadoo” in a Spanish all-inclusive once a year – the height of aspiration they permitted. (“Are you going on holiday for one week or two, Mark?” they would ask. “Oh, just the one,” I’d reply “Ramón doesn’t like flying.”) It’s a tough lesson learning your guardians aren’t infallible owing to their working-class status. Think of poor Toto being spirited into Miss Gulch’s basket on the threat of the sheriff seizing the family farm.

In the first dreaded borstal I attended – a school so rough, even the teachers had to be dropped off and collected by their parents – a classmate threw a hulking silver padlock at me, one December. They’ll probably make it a ruby padlock in the film of my life. Shows up better in Technicolor. Nursing a wounded forehead, I was in a different academy by January. Still not an elite one, mind, where I would’ve thrived – where every doctor, knowing the tuition was within the parents’ means, urged them to send me. The Mother invented all manner of conjecture to placate Little Man Tate. Her friend Helen’s boy was bullied in Terenure College. The neighbour’s son who went to Stratford was a Luas driver now. And the Father’s pal whose daughters were in the Institute was swindling the tax man to pay for it! “If you wanted it Bad Enough, you’d do it despite the school.”

Which I did. But my formative years were spent in a fool’s paradise. I thought all I’d need do was click a ruby padlock together and my problems would be solved. Nobody’s coming to rescue you, mes chers. Even though I’m “22” now – oh, shut up! Jessica Chastain claimed she was “29” until she had dentures fitted – my sole ambition is to be a substantial person who’s “in” with the Better Sort. But The Wizard of Oz proves that no such people exist: the muckety-mucks are every bit as ineffectual as Dorothy’s folks. Salman Rushdie pined that Oz is a film whose “driving force is the inadequacy of adults, even of good adults, and how the weakness of grown-ups forces children to take control of their own destinies, and so, ironically, grow up themselves”. Substitute “children” for “gay men” (or “Other Bus-ers” in Mark-ism). And while, of course, we wish things had worked out differently; one learns to appreciate all the good their kin did for them. (“I had the measles once, and Aunt Em stayed right by me every minute.”) I certainly never went hungry.

To my mind, Em’s devotion anchors the picture although it’s not immediately apparent. Remember her calling out for Dorothy during the twister? Or her tender bedside presence at the end? What about the moment when she gives Miss Gulch what-for, readily defending her niece like a lioness. “Almira Gulch, just because you own half the county doesn’t mean that you have the power to run the rest of us. For twenty-three years, I’ve been dying to tell you what I thought of you, and now... well, being a Christian woman, I can’t say it!”

Clara Blandick’s performance – like Margaret Hamilton’s – was barely mentioned in contemporary reviews. “You don’t receive a lot of glory playing mothers and aunts and gossips,” she accepted. In semi-anonymity, Blandick trudged on. Her later appearances included Heaven Can Wait with Gene Tierney and A Stolen Life with Bette Davis. But the remainder of her films, in which she largely goes uncredited, are known only to scholars. She retired in 1950 and went into seclusion in a modest room at the Hollywood Roosevelt. Throughout the decade, her body became crippled as her eyesight deteriorated. Issues which came to a head on New Year’s Day 1962. Her physician’s pronouncement? Total vision loss. Unable to cope with the diagnosis, Miss Blandick began to slowly relieve herself of her possessions. By Palm Sunday, her plan was complete.

After attending Holy Week services at her church, Aunt Em prepared for her swan song. She laid out her resumé, alongside mementoes of her stage and movie career. She placed photographs and scrapbooks in prominent places. To make doubly sure that the fatal dose of sleeping tablets she’d ingested would serve their purpose, she tied a plastic bag around her head. Hair neatly coiffed and dressed in an immaculate blue dressing gown, Clara Blandick lay down among remembrances of a life well-lived.

Later that day, her landlady discovered this letter:

“I am now about to make the great adventure. I cannot endure this agonizing pain any longer. It is all over my body. Neither can I face the impending blindness. I pray the Lord my soul to take. Amen.”

Look, I get that there’s sadder things than arthritic blind-as-a-bat eighty-five-year-olds choosing when to make their exit. But the circumstances of her departure are utterly compelling. Clara Blandick’s suicide – like her moving appearance in a mythical film – ensured her name isn’t lost to history. I wish I could say something profound to end this composition, but all I can think of is this:

Vaccines don’t cause autism, but padlocks to the kisser might.

Read Next:

Madame President: Inside Bette Davis’s Ill-Fated Tenure as Academy Pooh-Bah

“They’ll probably make it a ruby padlock in the film of my life. Shows up better in Technicolor. “

Another gem from Mark - a ruby this time! *chefs kiss*